All hat, no cattle: 12 years of unfulfilled ‘mentality reform’ promises in Turkey

/By Mümtaz Murat Kök, Media and Law Studies Association (MLSA)

On 11 July 2022, the European Court of Human Rights (ECtHR or the Court) ruled that Turkey failed to execute the Court’s judgment in the case of Kavala v. Turkey. In its history, this is the second time the court has ever conducted infringement proceedings against a member state since Mammadov v. Azerbaijan. Considering this situation, it would be an understatement to call Turkey's non-implementation of the judgments of the ECtHR simply a problem.

In their article, lawyers Tatiana Chernikova and Denis Shedov discuss the same predicament in Russia. Among the reasons for non implementation of the ECtHR’s judgments by Russia, the authors list the lack of a specific institution responsible for the implementation of the ECtHR’s judgments. Though Turkey and Russia may appear similar when it comes to the average time leading cases have been pending implementation, unlike Russia, Turkey does have a specific institution responsible for implementing the judgments of the European Court of Human Rights.

Foto credit: Filiz Gazi

Non-implementation as ‘sickness’, ‘mentality reform’ as cure

“The Department of Human Rights" was established within the Ministry of Justice by Executive Decree no. 650 dated 26 August 2011 and published in the Official Gazette to amend Article 13 of the Law No. 2992 on the Organization and Duties of the Ministry of Justice. Among other things, the department has been tasked “to perform duties and procedures in the enforcement of the judgments of the Court finding violations against the Republic of Turkey.” Not long after, the department’s jurisdiction was extended through a protocol signed between the Ministry of Justice and the Ministry of Foreign Affairs on 14 November 2011. As per Article 5/1 of said protocol, the department has been entrusted with carrying out all procedures in the implementation of the judgments of the ECtHR.

In the press conference held after the signing of the protocol, the ministers, among others, answered to the question “Why are the judgments of the Court not implemented?” Then Foreign Minister Ahmet Davutoğlu acknowledged that Turkey’s record before the European Court of Human Rights is “a sign of sickness.” According to Davutoğlu, a systematic illness caused the ever increasing number of applications to the Court from Turkey. Following his diagnosis, the minister prescribed “procedural” and “mentality reform.” In terms of procedural reforms, he praised the protocol that had just been signed and added that “even legislative changes” may be considered if deemed necessary in the future. With the new protocol, so the minister claimed, the way to any such change had been opened as a preventative measure. In terms of “mentality reform”, Davutoğlu declared that henceforth, there would be no more excuses for the mistakes of previous governments which gave way to violations in the first place and against which the AKP government now still had to submit “defenses” in the course of the implementation process. Instead of “defending a wrong judicial decision,” the minister continued, Turkey would start “cleaning up its act” and consider “all kinds of alternatives” to decrease the number of applications before the court on matters of fundamental freedoms.

12 years after these bold statements, no signs of an actual mentality reform are in sight. On the contrary, not only does the current government defend the mistakes of the past, in practice they enthusiastically add up to them. The Oya Ataman Case, which is one of 133 leading cases pending implementation by Turkey, is a perfect example of this gangrenous reality.

The Oya Ataman Case

In 1997, the Ministry of Justice introduced a new project for the construction of “high security” prisons across Turkey. The government of the time claimed that these prisons, widely known as “F-Type prisons”, introduced more effective and more humane methods of prison administration. Several reports by human rights organizations (e.g. a report by the Turkish Medical Association) pointed out that these prisons, which rely on the isolation of political prisoners, are not compatible with human rights.

On 22 April 2000, eight months before the so-called “Operation Return to Life”, the Istanbul Branch of the Human Rights Association planned a press statement in Istanbul’s Sultanahmet Square in order to protest F-Type prisons. A group of 40 - 50 human rights defenders and activists arrived at the square around noon. They were immediately ordered by the police to disperse under the claim that they might “disrupt public order” at that busy time of the day. When the demonstrators refused to scatter, the police resorted to pepper spray and took 39 demonstrators into custody. Among those who were detained was lawyer Oya Ataman. After the Turkish authorities had refused to initiate proceedings against the police, he filed an application with the European Court of Human Rights in 2001.

On 5 December 2006, the European Court of Human Rights ruled that the intervention of the police to a peaceful demonstration violated the applicant’s freedom of assembly. In its judgment, the court granted that there may be regulations requiring prior notification about planned demonstrations to the authorities but also noted that these requirements must not serve as “a hidden obstacle to the freedom of peaceful assembly.” The court established that the interference with the applicant’s freedom of assembly was “prescribed by law”, namely Law no. 2911 on Demonstrations and Assemblies. However, being “struck by the authorities’ impatience in seeking to end the demonstration”, it found such interference unnecessary in a democratic society.

It is important to mention here that three years before the ECtHR’s judgment, an Istanbul court had sentenced 38 of the demonstrators of the event in question to 1 year 8 months in prison, in addition to 91 million Turkish Liras of judicial fine. The first instance court ruled not to suspend the prison sentences for three of the human rights defenders on the grounds that “they are incorrigible” and that they show no sign of remorse.

PHOTO credit: Hayri Tunç

The ECtHR’s judgment in the Oya Ataman Case has been pending implementation since 5 March 2007. In fact, Oya Ataman’s case has become the leading case of a group of cases concerning violations of the right to freedom of peaceful assembly, including the prosecution of participants in demonstrations and the use of excessive force to disperse peaceful demonstrations.

‘The problem is not the law, but it’s application’

Contrary to the statements made 12 years ago and in defiance of reality, in their latest Action Plan submitted to the Committee of Ministers on 16 January 2023, the authorities claimed that “the underlying reason for the violations at hand is the application of the law in practice rather than its substantive provisions.” Showing how far they have come from the statements made in 2011, the authorities even gave a “warning” to the Committee: “considering that there is no deficiency in the Turkish legislation, the Government of Türkiye would like to note that insisting on a legislative amendment would lead to excess of power.”

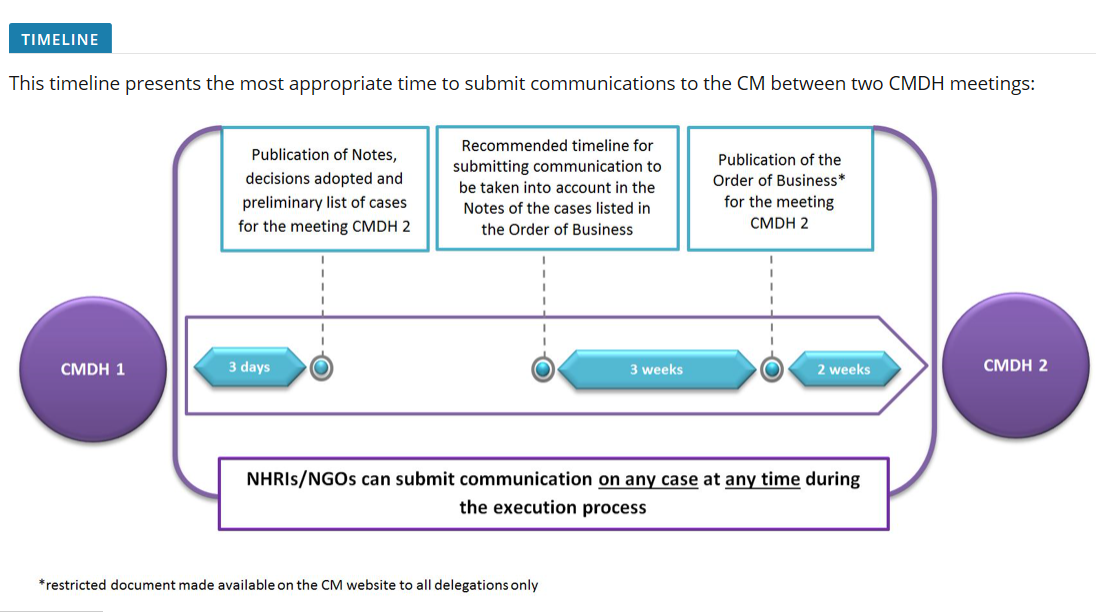

The repetitive cases in this group and daily experiences prove what the Committee of Ministers has insistently stressed upon: the problem is the law. The very same legislation that was used to sentence human rights defenders who went to the Sultanahmet Square in 2000 to protest inhuman prisons is used against protestors today. In its latest submission to the Committee, the Media and Law Studies Association (MLSA), through data gathered by monitoring of freedom of assembly trials, has put forward how the Law itself (more specifically Articles 9, 10, 16, 17, 22, 23, 28-32) still gives way to violations. These articles, which are vaguely worded, allow interpretation contrary to the Convention standards and make it possible for the authorities to declare peaceful assemblies “illegal”, impose arbitrary bans and sentence individuals for attending peaceful demonstrations. The arbitrary restriction of freedom of assembly, MLSA argued, can be seen in the radically different attitude of the authorities towards the Saturday Mothers/People and the group called “the Defense of the Islamic Movement” both of which wanted to hold demonstrations in front the Çağlayan Courthouse in Istanbul. Article 22 of the Law no. 2911 stipulates that demonstrations in the vicinity of certain public buildings such as the parliament and courthouses are “forbidden.” In its submission, MLSA shared with the Committee that whereas Saturday Mothers who wished to make a press statement before the September 21st hearing of their trial, were violently dispersed by the police, the group called “the Defense of the Islamic Movement” who are also known for their hate campaigns against LGBTİ+ were allowed to hold a demonstration on 21 December 2022 despite the fact that they were chanting “Death to infidels!” In the eyes of the authorities, Saturday Mothers/People were a bigger threat to public order. Therefore we believe these submissions - which have been prepared with the input/support of EIN - are one of the ways to be a crucial instrument to contribute to the long-winded implementation process of ECtHR judgments.

Another way to support the implementation of the Court’s judgments is through strategic litigation. In addition to individual legal support, MLSA files lawsuits which serve not only to protect freedom of assembly but also journalists who record the violations of freedom of assembly. One such example is the General Directorate of Security’s circular published on 27 April 2021, which attempted to ban audio-visual recordings during public demonstrations. Reviewing the lawsuit filed by MLSA, the Council of State ruled to suspend the execution of the circular on the grounds that it violated Articles 7 (legislative power) and 13 (restriction of fundamental rights and freedoms) of the Constitution.

Final remarks

Especially since the Gezi Park Protests, freedom of assembly in Turkey is a freedom only selected groups are allowed to enjoy. The blanket bans imposed in Batman and Van or on Saturday Mothers who have been arbitrarily banned from gathering at the Galatasaray Square where they had gathered since 1995 to demand justice for their loved ones who have been forcibly disappeared, are all made possible by the Law no. 2911. It is clear that the Law no. 2911 needs to be amended. However, the amendment of the Law requires a profound mentality reform.

However, in a political climate in which the president himself repeatedly defied the Court’s judgments, it would be naive to expect such a reform. Emboldened by such actions of high level politicians as well as other member states which continue to undermine the Convention system, the authorities do not even bother to provide accurate statistics which would clearly demonstrate that the application of the law is not the problem.

Therefore the Committee should insistently demand Turkey to amend the law and should supervise the implementation of the Court’s judgment in the Oya Ataman Case more frequently. Also important, the Committee should take individual examples such as Saturday Mothers into consideration and demand explanation on these symbolic cases. The ongoing legal harassment of Saturday Mothers as well as arbitrary restrictions imposed on them would provide the Committee with a crystal clear picture that Turkey is trending backwards with regards to freedom of assembly.