Justice Delayed and Justice Denied: Report on the Non-Implementation of European Judgments and the Rule of Law

Respecting and implementing court judgments is a basic test of any State’s commitment to the rule of law. In Europe, this applies with particular force to the judgments of the European Court of Human Rights (ECtHR) and the Court of Justice of the European Union (CJEU), which safeguard fundamental rights and the integrity of the European legal order.

The fourth edition of the European Implementation Network (EIN) and Democracy Reporting International (DRI) joint report ‘Justice Delayed and Justice Denied’ examines how EU Member States implement the judgments of Europe’s two apex courts. Building on previous reports, it updates the data to 1 January 2025, expands the country coverage, and refines both the quantitative and qualitative assessments.

The focus remains on judgments with the greatest systemic impact. For the ECtHR, the analysis is based on “leading” ECtHR judgments, designated by the Council of Europe’s Committee of Ministers to identify human rights issues for the first time in a country, often revealing structural or systemic problems and therefore requiring broader reforms. For the CJEU, the report concentrates on rulings related to the rule of law, including justice systems, anti-corruption, media freedom and pluralism, and institutional checks and balances.

Across much of the EU, the gap between legal victories before European courts and real-world change is widening. Non-implementation, partial implementation, and protracted delays are not isolated anomalies but entrenched patterns in several member States, and frequent feature in others. This non-compliance is also increasingly accompanied by open or implicit contestation of European courts’ authority by political actors and, at times, by top national courts. The practical consequence is that serious violations of human rights and the rule of law continue for years, sometimes decades, after they have been formally recognised in Strasbourg or Luxembourg.

Report recommendations

To halt and reverse the rule of law crisis, the EU has introduced, throughout the years, a series of policy measures, ranging from the annual rule of law review cycle, to targeted measures, such as withholding structural funds from countries with severe infringements of the rule of law. In 2022, following civil society calls for the EU’s rule of law reporting to take into account the non-implementation of judgments from the ECtHR, the EU Commission has included our data in its annual Rule of Law Report. This development allowed the EU to identify longer-term problems with the rule of law across all Member States that had previously been overlooked. Despite the measures, non-compliance continue to be a significant problem to address, and EU and Council of Europe institutions, as well as national authorities hold a central role in closing the gap between legal victories before European courts and real-world change is widening.

EIN and DRI set out the following recommendations to the European Commission and the Council of Europe

-

Make implementation of CJEU judgments, in the same way as the ECtHR judgments, a core metric in the Rule of Law Report, with systematic use of implementation data and clear country comparisons.

Systematically issue tailored country-specific recommendations based on ECtHR/CJEU implementation records, with particular focus on chronic underperformers (especially Bulgaria, Hungary, Poland and Romania)

Develop a public scoreboard or equivalent tool tracking national follow-up to ECtHR and CJEU case law (including preliminary rulings).

Use enforcement tools more decisively in cases of persistent non-implementation (infringements, follow-up under Article 260 TFEU, and, where relevant, budgetary conditionality).

Treat serious non-implementation as a priority topic in political dialogue with governments and parliaments, supporting pro-reform “compliance communities”.

Create or adapt EU funding lines (e.g. under CERV and other programmes) specifically to support implementation-oriented work by civil society, legal professionals and oversight bodies.n text goes here

-

Use the full political toolbox available to the Committee of Ministers (including enhanced supervision, debates and infringement proceedings) much more robustly and consistently in response to chronic non-implementation, to avoid its trivialisation.

Decisively tap into the potential created by the introduction of the complementary joint procedure between the Committee of Ministers, the Parliamentary Assembly and the Secretary General to respond to flagrant instances of resistance to implementation of ECtHR judgments.

Avoid premature closure of complex groups of cases before underlying structural problems are demonstrably resolved in law and practice.

Apply political and diplomatic pressure in a consistent way across all thematic areas (judicial independence, detention, discrimination, SLAPPs, etc.).

In line with the Reykjavík Summit pledges, deepen structured engagement with Ombuds institutions, NHRIs, equality bodies and NGOs, going beyond written Rule 9 submissions.

Increase resources for execution work – especially for the Department for the Execution of Judgments and related CoE cooperation projects – to ensure that budget increases for reducing the ECtHR judicial backlog do not undermine the implementation mechanism’s capacity to reduce its own backlog.

-

Make proactive use of Article 52 ECHR inquiries in states with entrenched non-implementation of key ECtHR judgments, to raise the political costs of inaction and press for concrete reform plans.

-

Consider prioritising, among various important means of action available, targeted Rule 9 communications when addressing implementation matters within the broader context of the mandate of the institution, as well as maximising the budgetary allocations concretely earmarked for the preparation and submission of such communications.

-

Adopt coherent national implementation strategies with clear timelines, responsibilities and parliamentary oversight, instead of ad hoc, fragmented measures.

Robustly undertake politically sensitive structural reforms flagged as required by ECtHR/CJEU judgments (e.g. in areas such as judicial independence, detention conditions, surveillance, discrimination) instead of settling for technical or cosmetic fixes.

Safeguard judicial independence and ensure that national courts are not hindered in consistently applying ECtHR and CJEU case law, including disapplying conflicting national norms where required.

Create and strengthen effective domestic remedies (preventive and compensatory) to address recurrent violations and reduce the flow of repetitive cases to Strasbourg and Luxembourg.

Summary of our findings

State Compliance Record with the European Court of Human Rights (ECtHR) Judgments

State of non-implementation of ECtHR judgments in EU member States (leading judgments as of 1 January 2025)

On the ECtHR side, the picture is one of growing backlog and slowing progress. As of 1 January 2025, there were 650 leading ECtHR judgments awaiting full implementation across EU member States, up from 624 in January 2024, and 616 in the year prior. Further, 45.7 per cent of leading judgments delivered in respect of EU States over the past ten years were still pending implementation, compared to 44 per cent at the end of 2023 and 40 per cent at the end of 2022. By end 2024, the average implementation time for leading ECtHR judgments concerning EU States has reached 5 years and 4 months, compared to 5 years and 2 months in 2023, and 5 years and 1 month in 2022.

-

Overall, since the first edition of the report in 2021, the number of pending leading judgments has increased by 8 per cent (from 602 to 650), the share of the open cases from the past 10 years by 24 per cent (from 37.5 per cent to 45.7 per cent), and the average implementation time by 23 per cent (up by a full year, from 4 years and 4 months). This is despite intensified Council of Europe–state cooperation to strengthen domestic implementation mechanisms, and the improvements achieved in cases where resistance to implementation is not rooted in a lack of political will.

The increase across all three indicators is not a simple linear trend but reflects several underlying dynamics. Each year, the Committee of Ministers has closed fewer leading cases than it has received for supervision in respect of EU States, and it has generally been easier to close newly delivered cases than older leading judgments that identify complex or structural problems. In many of the pending cases, reforms were undoubtedly under way or partially completed by 2024; however, the persistent failure to fully resolve long-standing structural issues – often clustered around the same sensitive themes – continues to jeopardize the rule of law in the States concerned and to generate new repetitive applications, undermining rule of law and the effectiveness of the ECHR system as a whole.

-

Non-compliance persists because many fundamental reforms needed to fix the problem are routinely blocked. This is despite unprecedented national and international attention to ECtHR implementation and intensified cooperation to improve national implementation mechanisms, which has produced results where lack of political will is not the primary obstacle.

Governments often avoid changes expressly, or they unduly delay them, in particular in relation to the above-mentioned thematic areas that are considered sensitive, leaving crucial legal and policy updates to stagnate. Political deadlock then locks the system in place. In some countries, even the judiciary becomes part of the problem: when top courts are shaped by political influence, judges can delay or obstruct implementation, shutting the door on genuine progress.

In illiberal contexts, as is the case of Hungary, compliance is also the result of a cost-benefit analysis. Issues that carry immediate political costs – such as restrictive minority-rights policies – are treated as non-negotiable as they are central to the regime’s electoral appeal. By contrast, reforms that touch upon deeper power structures – for example those concerning the independence of the judiciary – are often managed through superficial or purely symbolic changes that preserve the status quo.

-

Non-compliance puts the entire Convention system under real strain and threatens its important acquis. When governments ignore Strasbourg rulings without consequences, it sends a message that respecting human rights judgments is optional. This erodes the rule of law and weakens the authority of the ECtHR, leaving people unsure whether their rights will be protected in the same way across Europe. Instead of one coherent system, we get fragmented standards and uneven levels of protection from one country to the next. And behind these systemic issues are real people: thousands continue to suffer because the violations identified by the Court are not properly addressed.

On a grimmer side, Bulgaria, Hungary, Italy, Poland and Romania continued to be the most struggling implementers in 2024. Romania continued to have the highest number of leading judgments pending implementation (111), whereas Hungary remained the State recording the highest rate of leading ECtHR rulings rendered in the last ten years still awaiting implementation – 74 per cent. For eight countries - Bulgaria, Hungary, Italy, Malta, Poland, Portugal, Romania and Slovakia - over 50 per cent of the leading judgments rendered against them in the last ten years were yet to be fully implemented at the end of 2024. Ten EU member States (Belgium, Bulgaria, Czechia, Greece, Hungary, Italy, Lithuania, Malta, Poland and Romania) had, in 2024, cases that had been pending implementation for more than 15 and up to 24 years. In two member States, Portugal and Slovakia, the overall implementation record worsened, shifting from moderate to moderately poor, and from poor to problematic, respectively.

There were, however, notable positive developments. Sweden, Austria, Denmark, Estonia, Finland, Luxembourg and Slovenia all presented an excellent or very good overall implementation record at the end of 2024. Austria, Cyprus, Finland and Germany improved their overall implementation scores, with Finland coming close to eliminating its long-standing backlog of leading judgments within two years (from nine cases to one). Czechia stands out as a particularly important example: the creation of a robust execution coordination authority a few years ago and, most importantly, the consistent capacity of the latter to move beyond a defensive or “litigious” approach once a new judgment enters its implementation phase has enabled the country to weather a strong influx of new violation judgments last year while maintaining rapid implementation and a solid overall record. Finally, Lithuania provided in 2024 a near-ideal example of full and effective implementation of a demanding ECtHR case. In the Macatė judgment, concerning the censorship of a children’s book depicting same-sex relationships, all necessary measures – including legislative change brought about following the Constitutional Court’s intervention – were adopted within less than two years, illustrating what timely and comprehensive execution can look like.

Thematically, the implementation problems before the ECtHR concentrate in a few sensitive areas. The most persistent gaps concern judicial independence and fair trial rights, where politicised councils, flawed appointments and abusive disciplinary proceedings against judges remain unresolved. Long-standing structural violations also persist in detention and prison conditions, with overcrowding, poor hygiene and weak remedies affecting large groups rather than isolated individuals. Judgments protecting vulnerable groups – including asylum seekers, LGBTIQ+ persons, Roma children and psychiatric patients – and cases linking environmental harm to Convention rights often encounter strong political or social resistance, leading to fragmented, delayed or purely cosmetic reforms.

State Compliance Record with the Court of Justice of the European Union (CJEU) Rulings Related to the Rule of Law

State of non-implementation of CJEU judgments in EU member States (rule of law-related judgments until 1 January 2025)

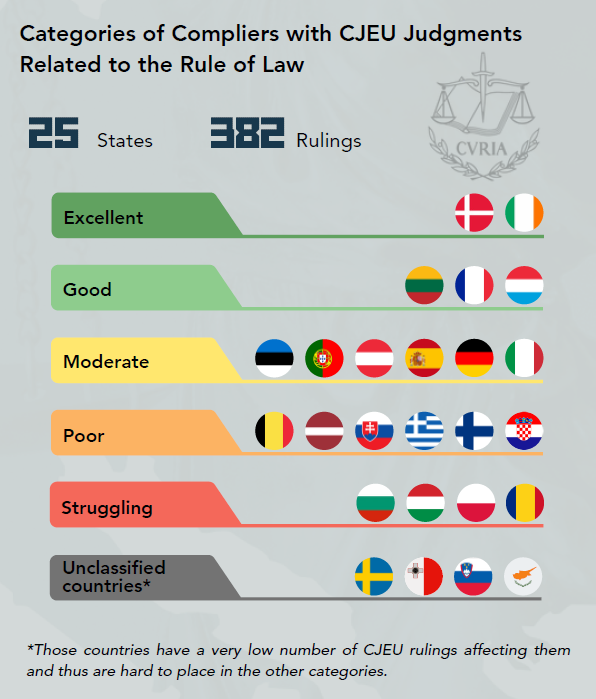

The CJEU picture is mixed but reveals similar underlying dynamics. The 2025 review assessed 382 rule of law-related rulings issued between 2019 and 2025 across 25 EU Member States. Of these, 223 (about 58 per cent) were fully complied with, 98 (about 25 per cent) only partially complied with, 35 (9 per cent) not complied with at all, and 26 (6 per cent) could not be conclusively assessed.

In total, over one third of CJEU rulings have not been fully complied with. Of the 133 rulings in this category, 83 (62.4 per cent) have been pending for more than two years, amounting to over a fifth of all rulings rendered (21.7 per cent).

-

Compared to last year, the data shows modest, but not substantial, improvement. The share of fully complied-with rulings rose from around 55 per cent (110 of 201 rulings) in the 2024 report to 58 per cent (223 of 382 rulings) in the 2025 report. The proportion of partially complied-with rulings remained broadly stable (24–26 per cent), while the share of rulings not complied with at all decreased slightly (from around 11 to 9 per cent).

This limited progress is largely driven by isolated improvements in a few states, most notably Poland, Bulgaria and Portugal. Overall compliance patterns, however, remain largely unchanged. Partial compliance continues to be the most alarming feature, especially where referring courts ensure case-level compliance but structural obstacles – such as legislative inertia, executive reluctance or open resistance from top courts – prevent full implementation. These barriers cause significant delays and account for a large share of outstanding rulings. The proportion of significantly delayed rulings has increased to 62.4 per cent of all pending rulings in this edition, compared to around 60 per cent in the previous report.

-

Delayed implementation typically stems from political reluctance to change laws and practices, or from political deadlock. In some cases, judicial resistance also obstructs implementation - especially when top courts are politically orchestrated.

-

The challenges are significant: when states fail to implement court rulings and face no consequences, they signal that compliance is optional, setting a dangerous precedent. Non-compliance undermines the rule of law, weakens the authority of the CJEU and creates uncertainty as individuals who can no longer rely on the uniform application of EU law. Divergent implementation results in fragmentation with different legal standards and levels of protection across the EU. Continued non-compliance also results in ongoing harm for thousands of individuals whose rights remain unprotected.

Hungary and Bulgaria continue to have the greatest problems, with very low full-compliance rates (25 and 18 percent, respectively), high levels of partial compliance (around 50 per cent), and significant delays: 84.6 per cent of Hungary’s and 52.9 per cent of Bulgaria’s not-yet-complied-with rulings have been pending for over two years. Poland and Romania also remain in the “problematic complier” category due to delayed justice-sector reforms.

Belgium and Slovakia qualify as poor compliers, displaying high levels of partial or non-compliance and/or prolonged delays. A middle group of moderate compliers includes Austria, Portugal and Estonia, with roughly 60–70 per cent of rulings fully implemented, and the remainder only partially complied with, many of them pending for more than two years. Germany, Italy and Spain meet several benchmarks for good compliance but are downgraded by recurring delays.

At the top of the spectrum, Ireland stands out as an excellent complier, having fully implemented all assessed rulings. France, Lithuania and Luxembourg maintain high full-compliance rates (above 80 per cent), with only minimal partial or delayed implementation. Smaller States with very few rulings – Cyprus, Sweden, Malta, Slovenia and Denmark – cannot be reliably categorised, as their small caseloads are statistically insignificant.

Thematically, non- or partial compliance is most pronounced in rulings touching judicial independence, access to justice and procedural safeguards, where reforms to disciplinary regimes, court governance and criminal procedure lag behind the Court’s requirements. Asylum and migration judgments are frequently implemented only at case level while restrictive legislation and practice remain largely unchanged. In data protection and surveillance, many States have yet to overhaul broad data-retention and access regimes that conflict with EU law. Cases on equality and non-discrimination likewise tend to trigger incremental, piecemeal adjustments rather than comprehensive reform, reflecting persistent legislative inertia and, in some instances, open resistance by political and judicial actors.

Previous editions of the report

Work supported by: