EIN Civil Society Briefing November 2022: France, Poland, and Turkey

/On 28 November 2022, EIN held the latest civil society briefing for permanent Representations of the Council of Europe, ahead of the 1451st Committee of Ministers Human Rights Meeting on 6 – 8 November 2022. The event was held in person in Strasbourg.

The Briefing focused on the following cases:

1. The J.M.B. and others v France case concerns prison overcrowding and poor conditions of detention and lack of an effective preventive remedy. This presentation was given by Prune Missoffe, Head of Analyses and Advocacy, and Julie Fragonas, Trainee Lawyer at Observatoire International des Prisons, Section France.

2. A. The Xero Flor W Polsce SP. Z.O.O. v Poland case concerns an infringement of the applicant company’s right to a fair hearing due to the domestic courts' failure, in the context of civil proceedings, to examine its argument that secondary legislation limiting its right to compensation was unconstitutional.

2. B. The Reczkowicz group case concerns an infringement of the right to tribunal established by law, due to the fact that the judges of the Disciplinary Chamber in the Supreme Court that dismissed the applicant’s cassation appeal against disciplinary penalty in 2019 were appointed in a deficient judicial appointment procedure involving the National Council of the Judiciary lacking independence from legislature and executive

2. C. Broda and Bojara v Poland case concerns an infringement of the right to access to court on account of the premature termination of the applicants’ term of office as vice-presidents of a regional court on the basis of temporary legislation in force between 12 August 2017 and 12 February 2018, which did not allow for examination either by an ordinary court or by another body exercising judicial duties.

Marcin Szwed, Lawyer at Helsinki Foundation for Human Rights, presented on these cases concerning Poland.

3. The Opuz group v Turkey case was presented by Elif Ege, Programme Coordinator at Mor Çatı, concerning the failure of the authorities to protect women from domestic violence, despite having been reasonably informed of the real and imminent risks and threats.

Overview of the case:

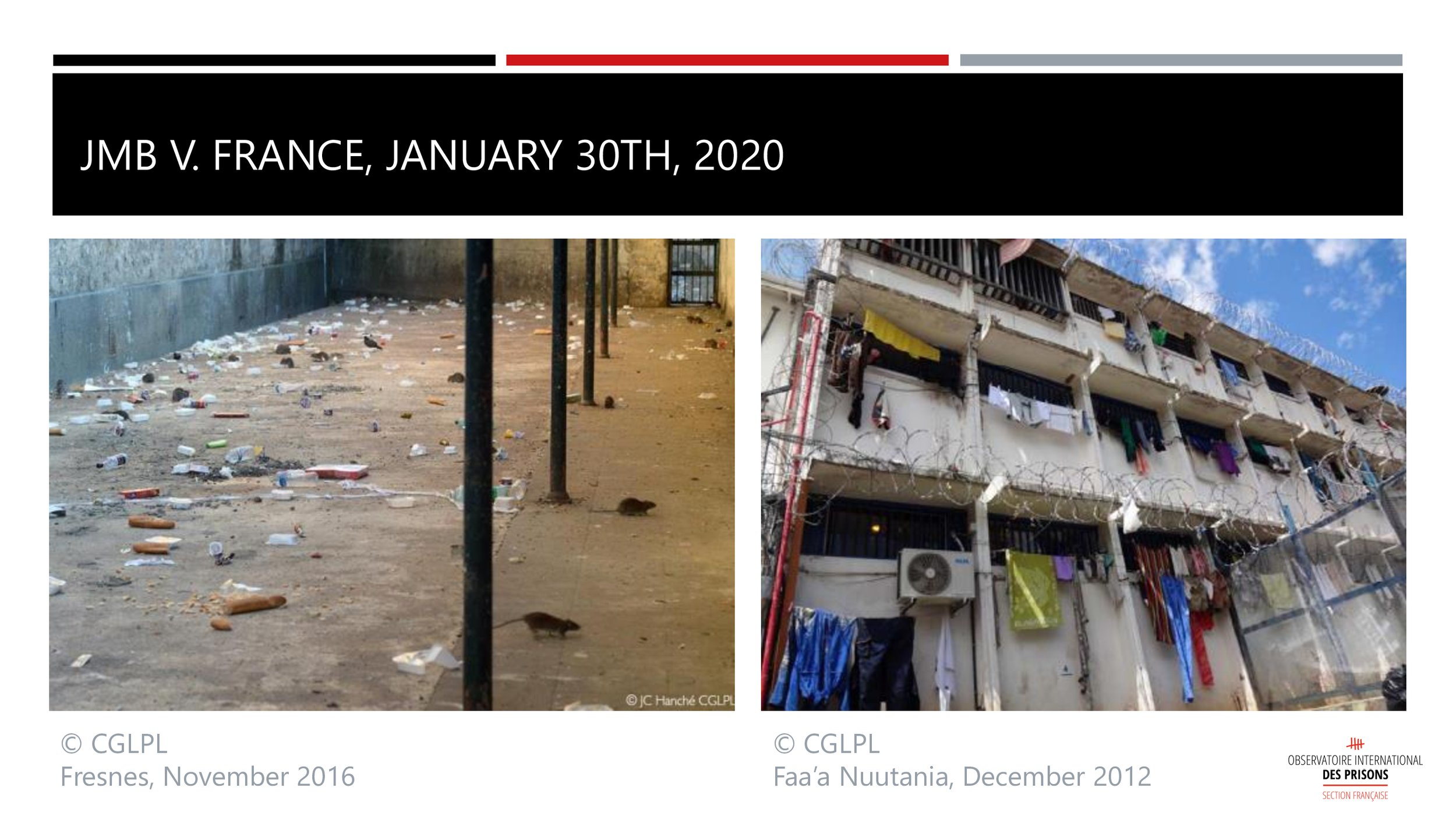

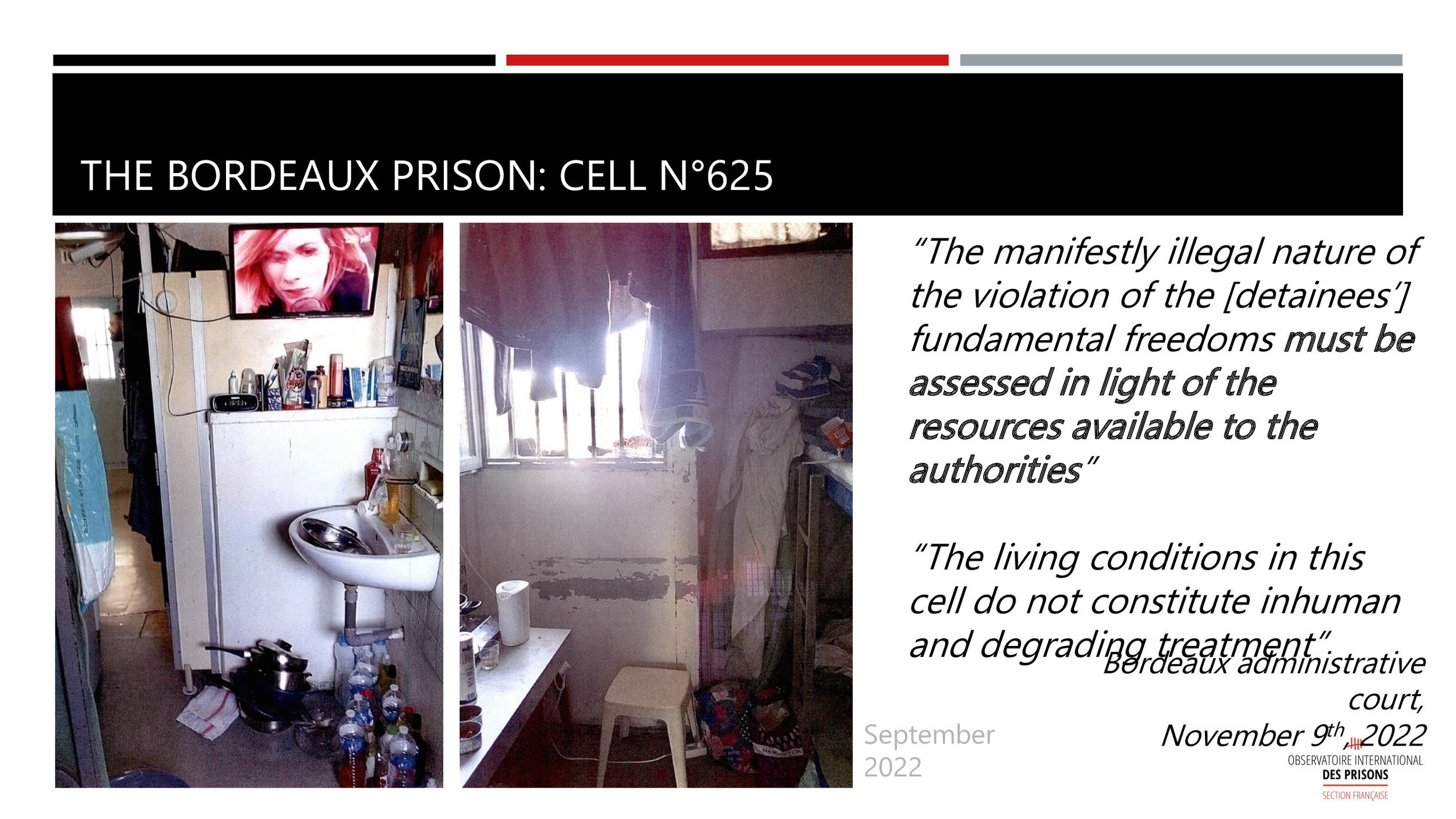

The J.M.B v France case concerns the structural problem of degrading treatment suffered by 27 of the applicants, due to prison overcrowding and poor conditions in the detention centres during different periods (2006 to date). It also concerns the lack of an effective preventive domestic remedy for 31 of the applicants, where administrative interim proceedings are ineffective in practice, due to the limited scope of the judge's injunctions and the difficulties in enforcing the overcrowding and dilapidation of prisons measures.

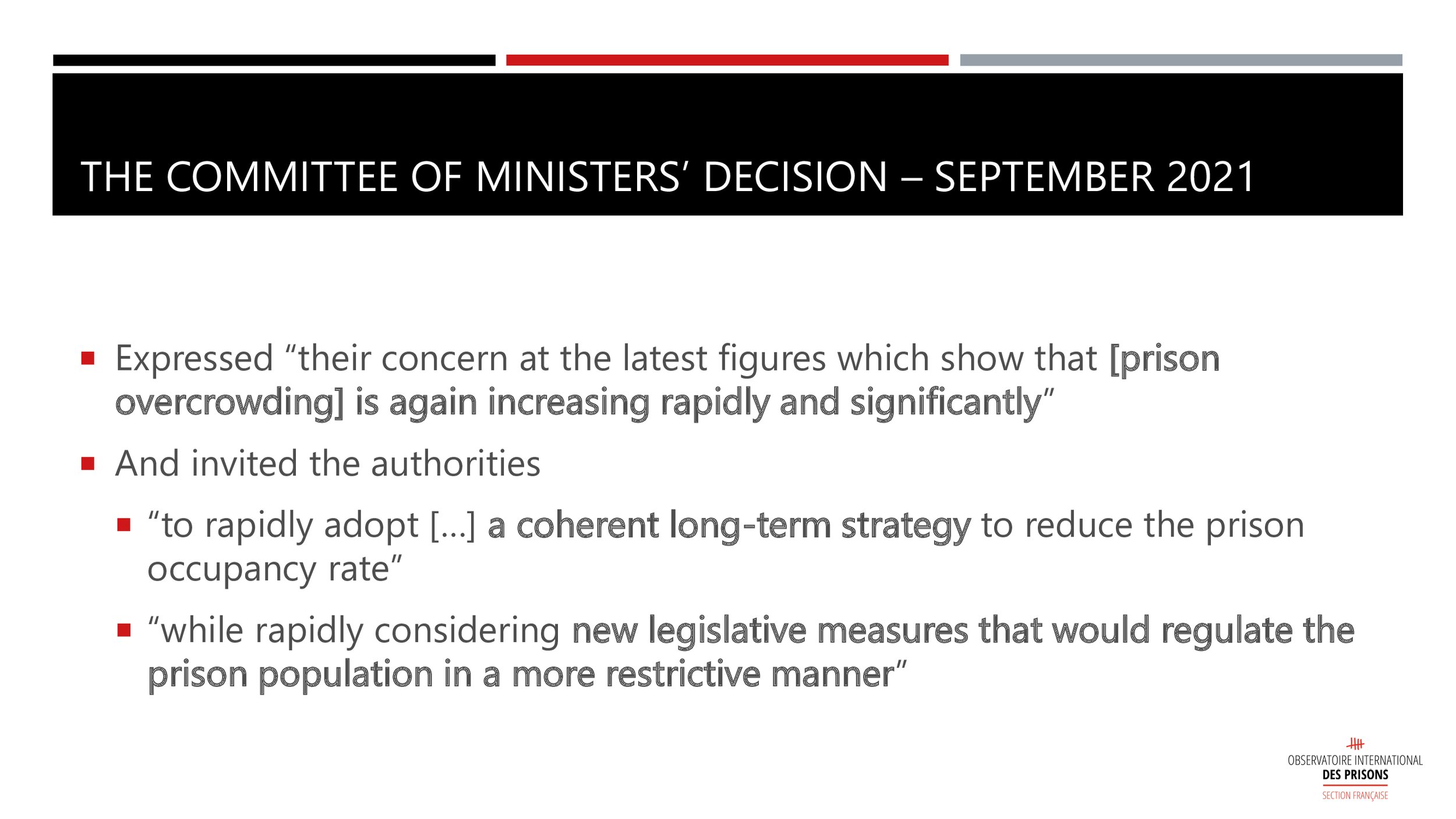

Observatoire International des Prisons reminded participants of the last Committee of Ministers Decisions in the case from 2021:

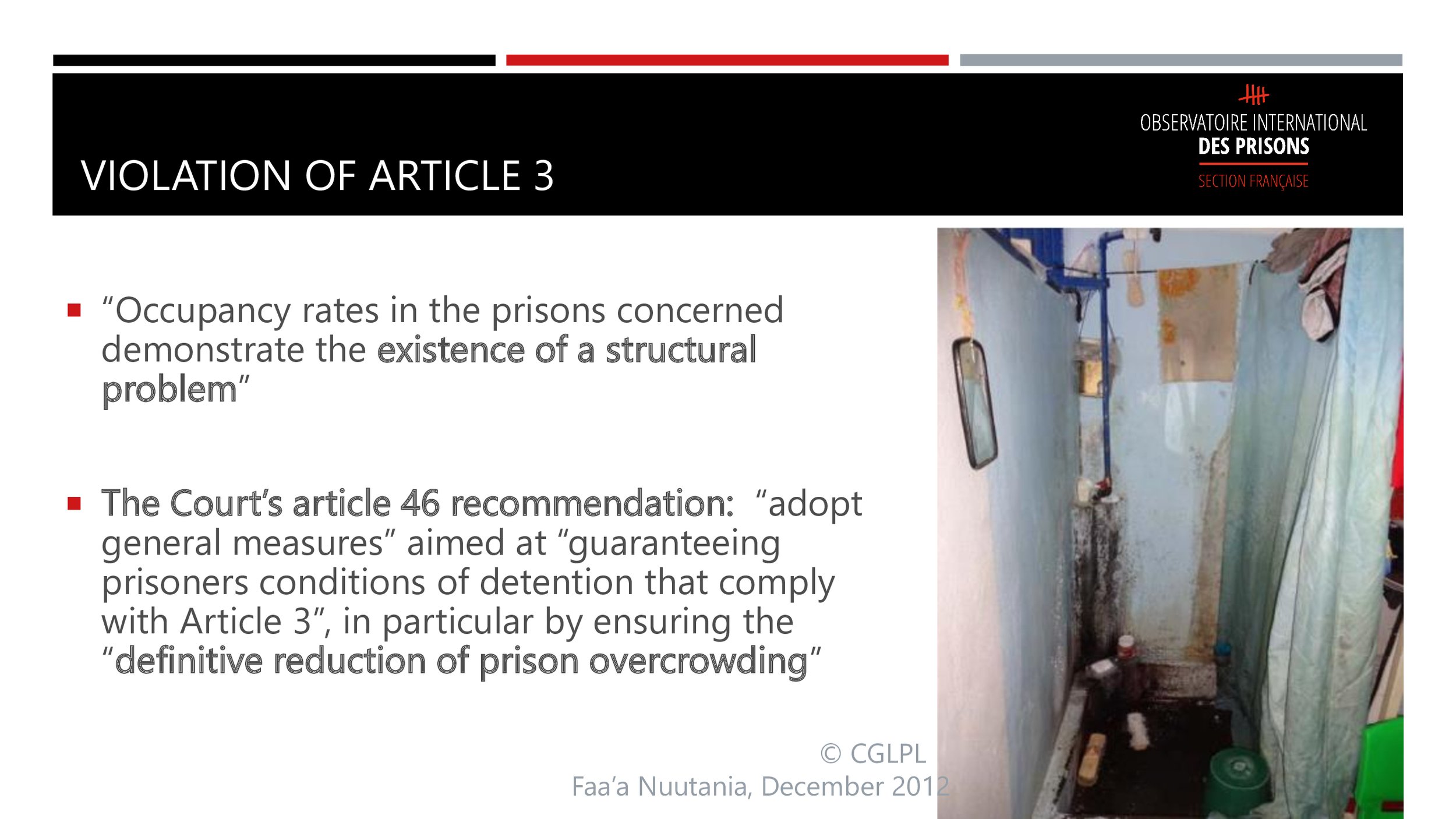

· Occupancy rates in the prisons concerned demonstrate the existence of a structural problem, where the Court recommended the government to adopt general measures aimed at “guaranteeing prisoners conditions of detention that comply with Article 3, in particular by ensuring the definitive reduction of prison overcrowding”.

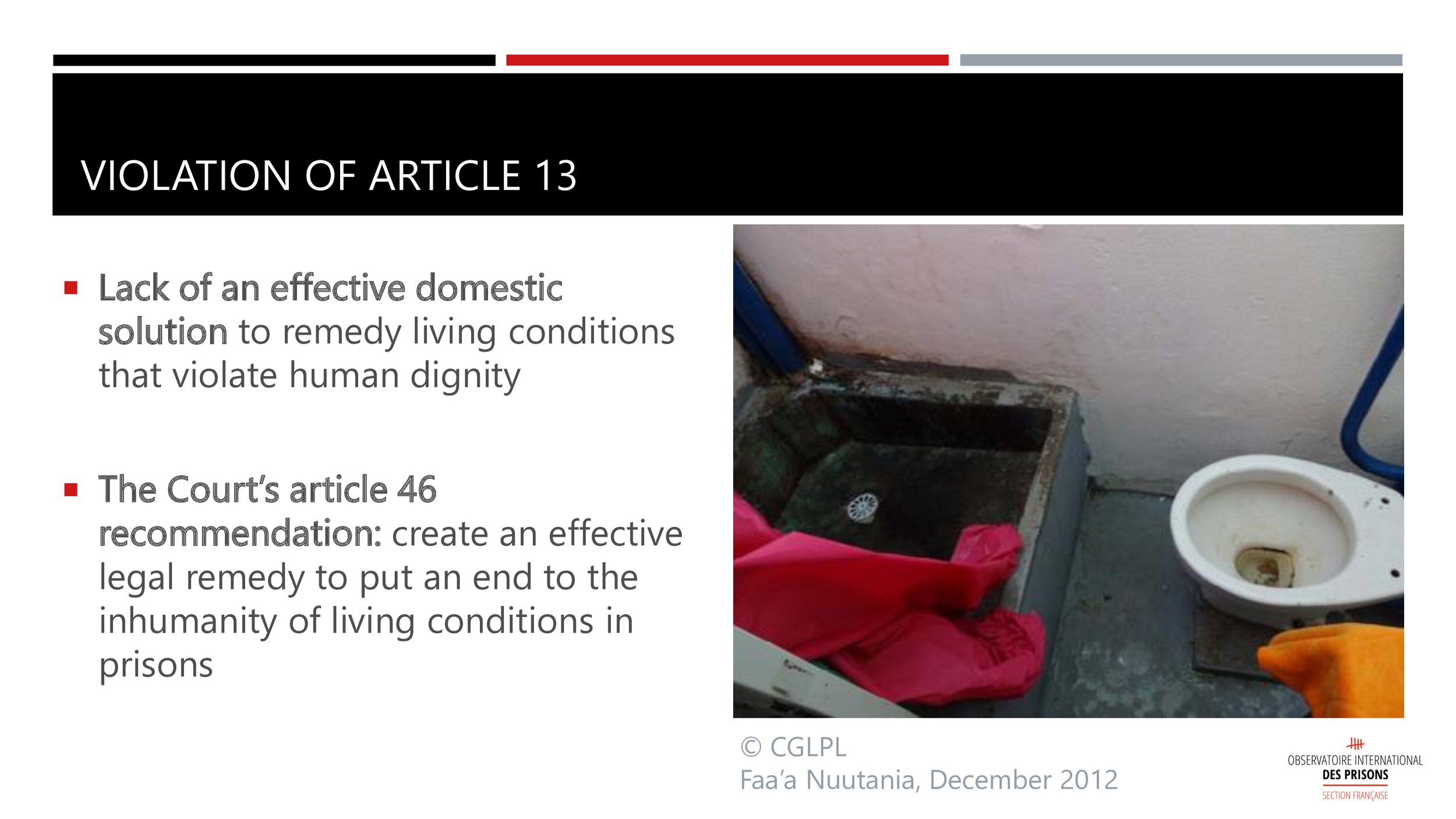

· Lack of an effective domestic solution to remedy living conditions that violate human dignity, and the Court recommended the government create an effective legal remedy to put an end to the inhumanity of living conditions in prisons.

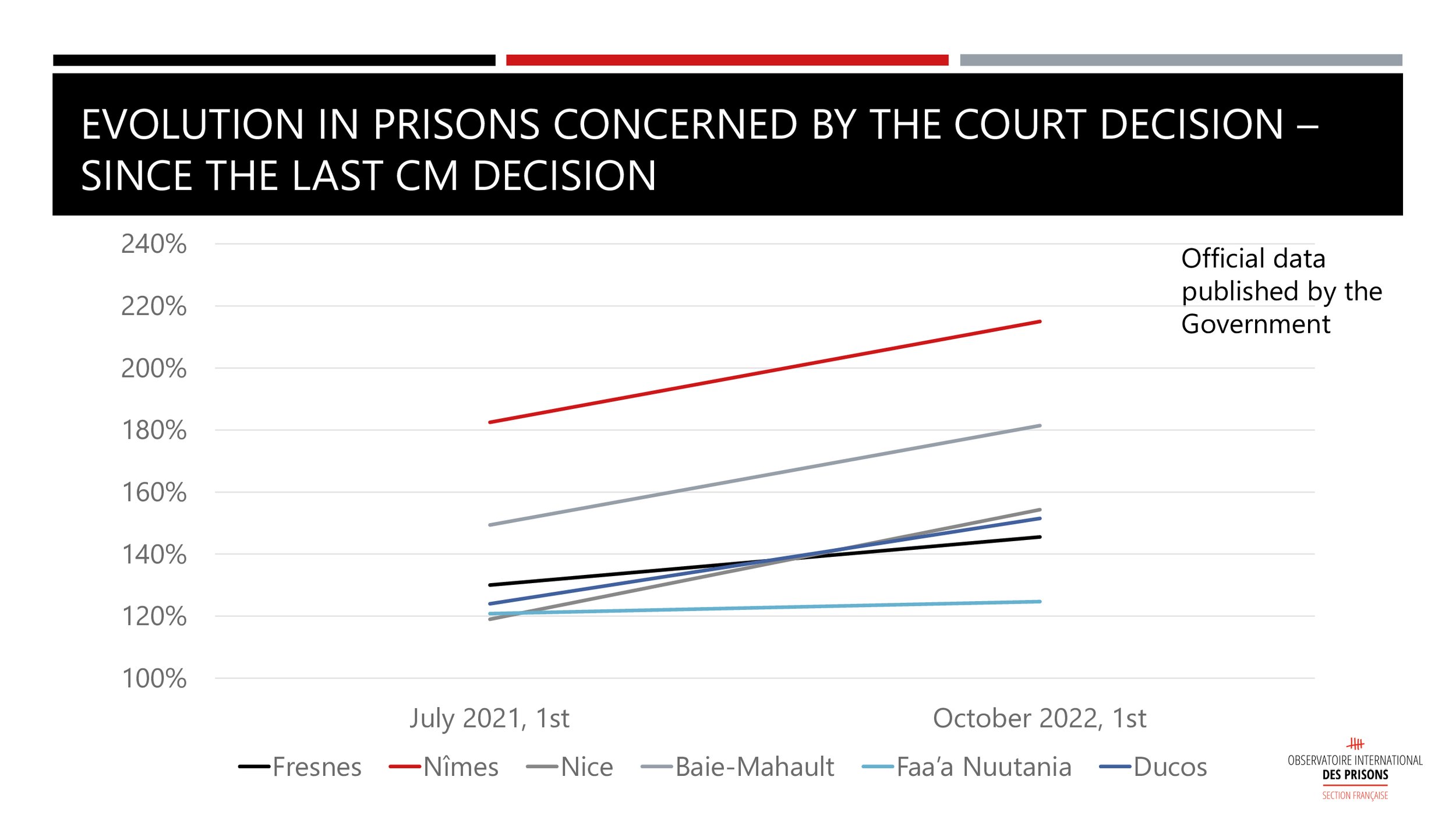

Observatoire International des Prisons provided information on recent developments concerning prison overcrowding since the Courts judgment:

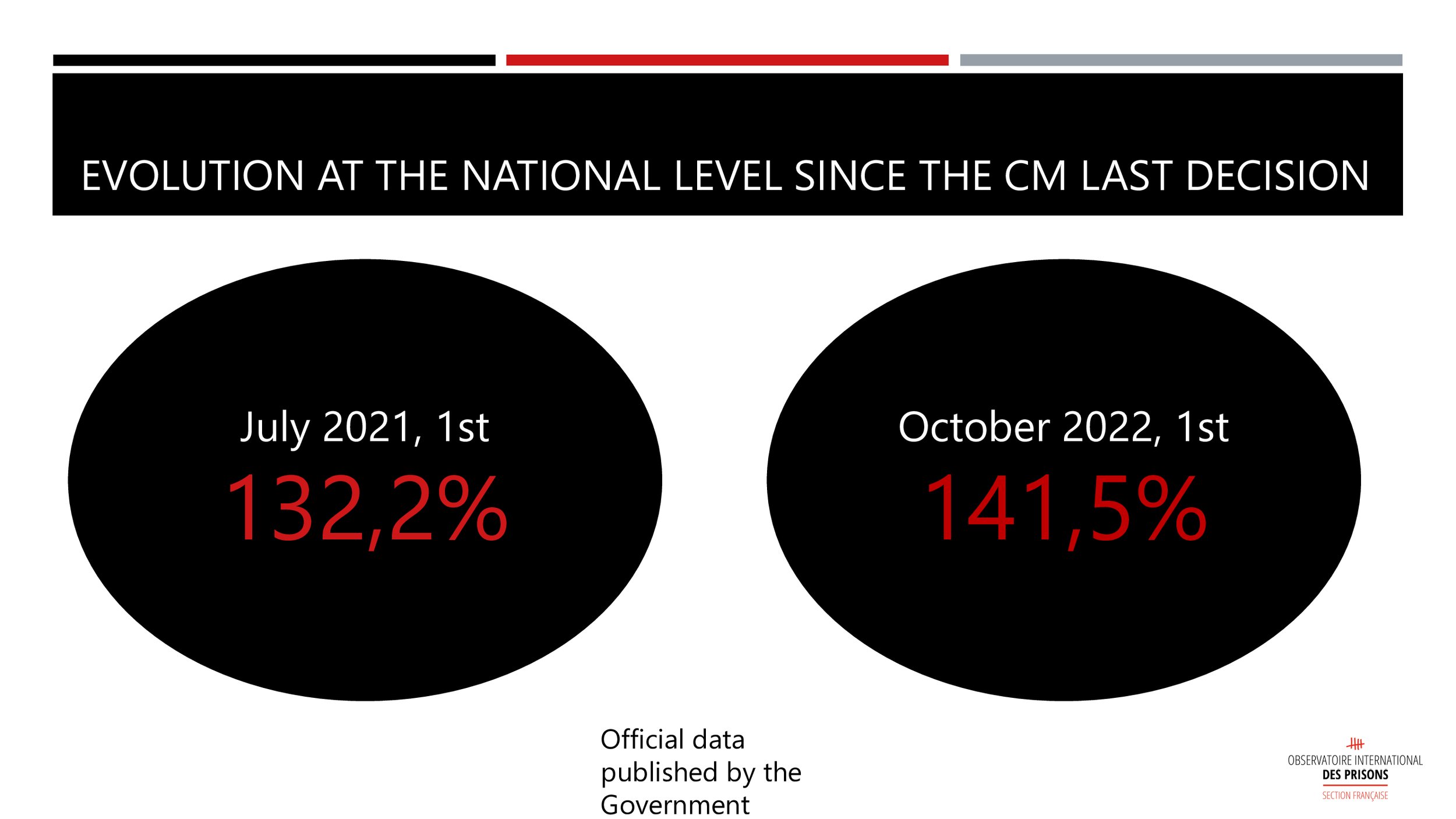

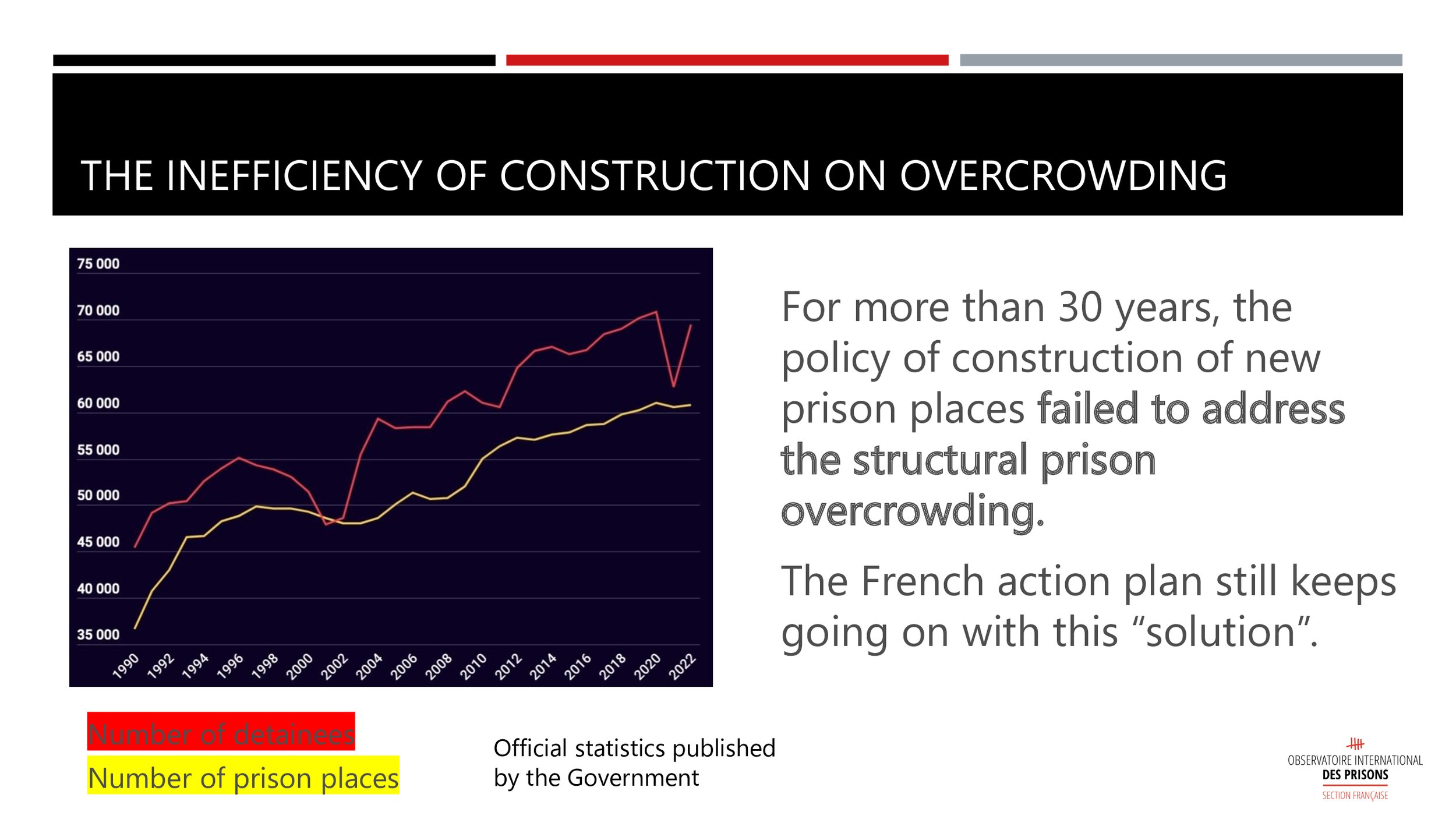

o Prison overcrowding is a worsening situation, as the occupancy rate has increased to 141.5 % since the last CM examination.

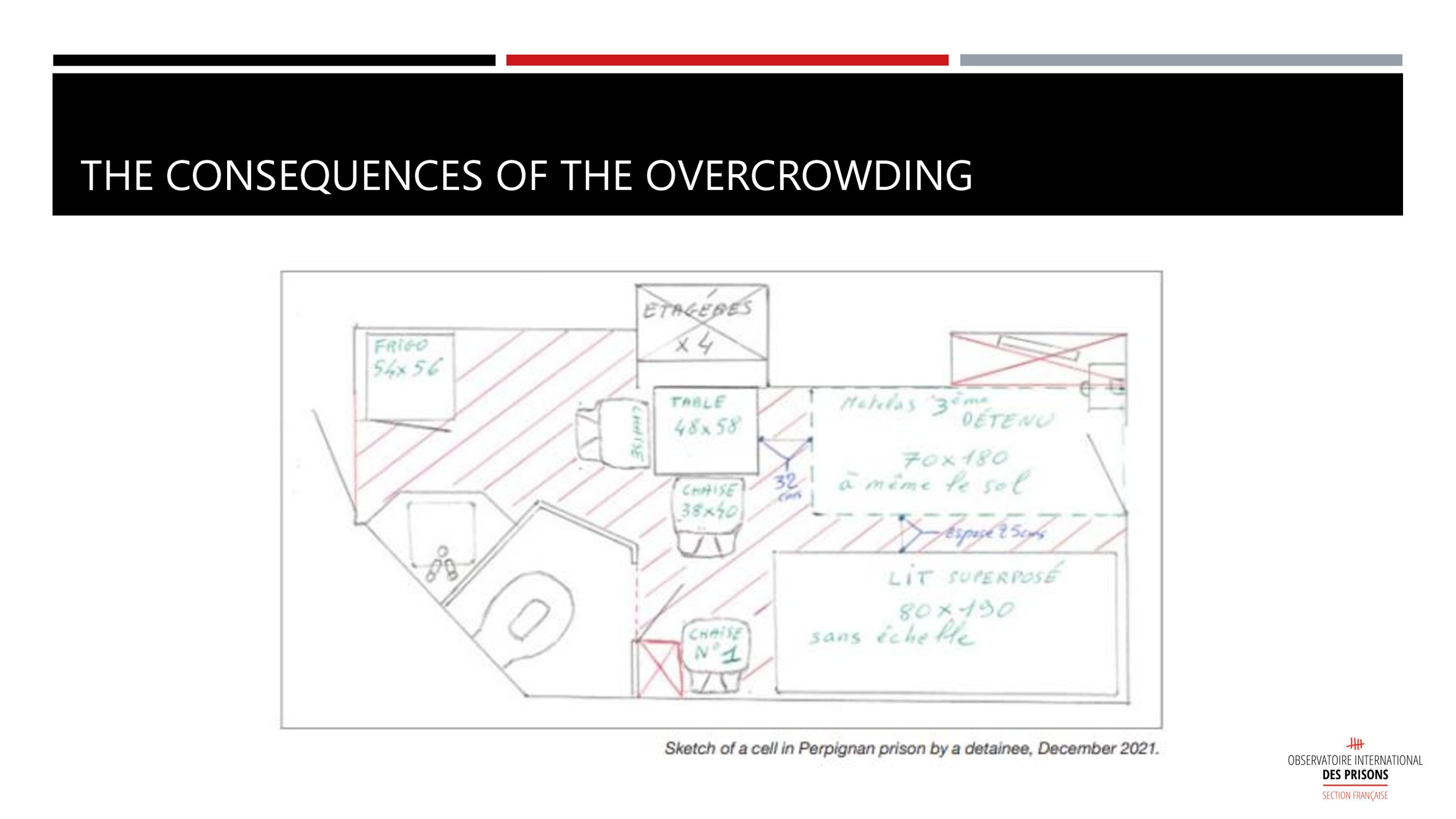

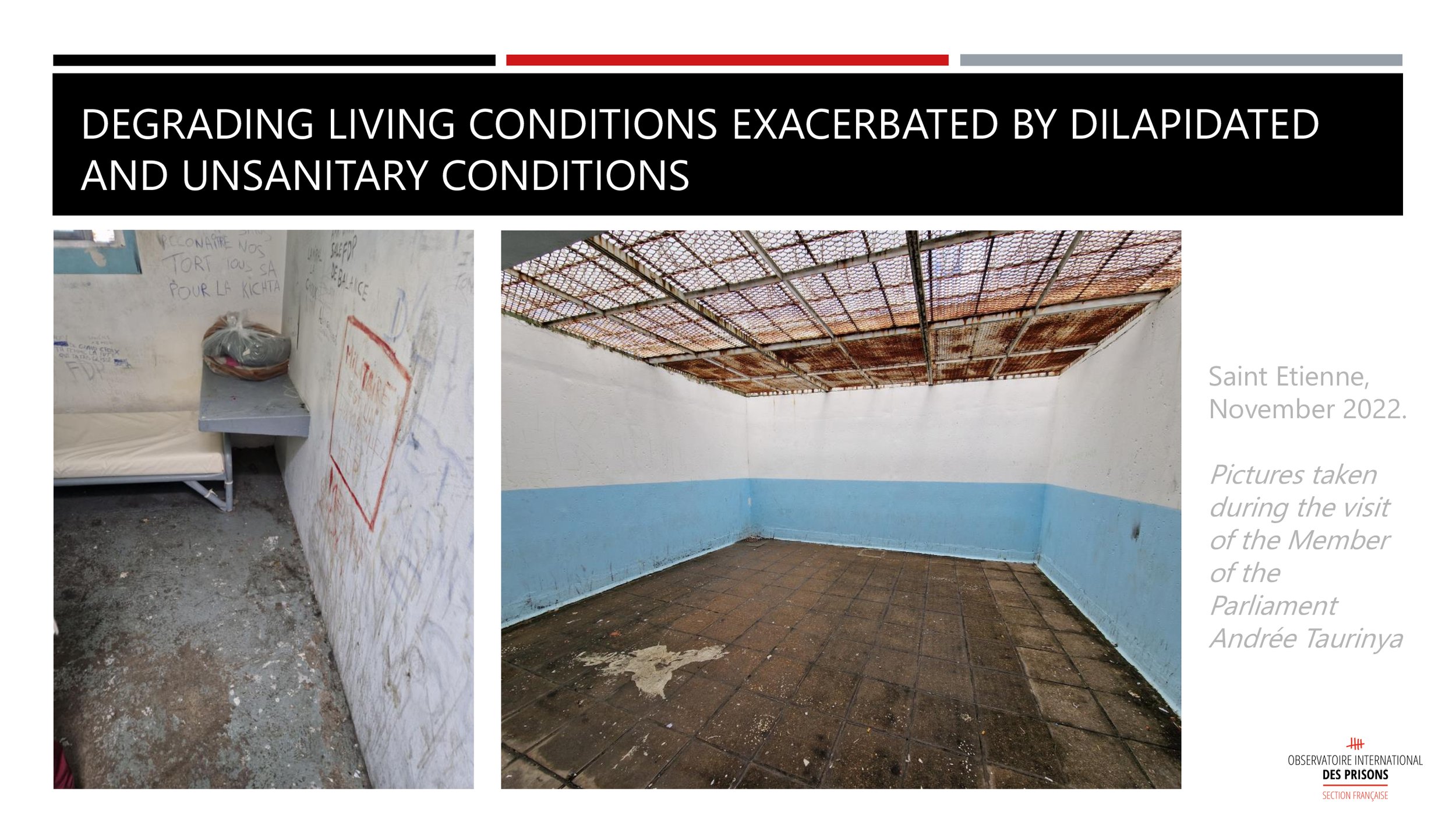

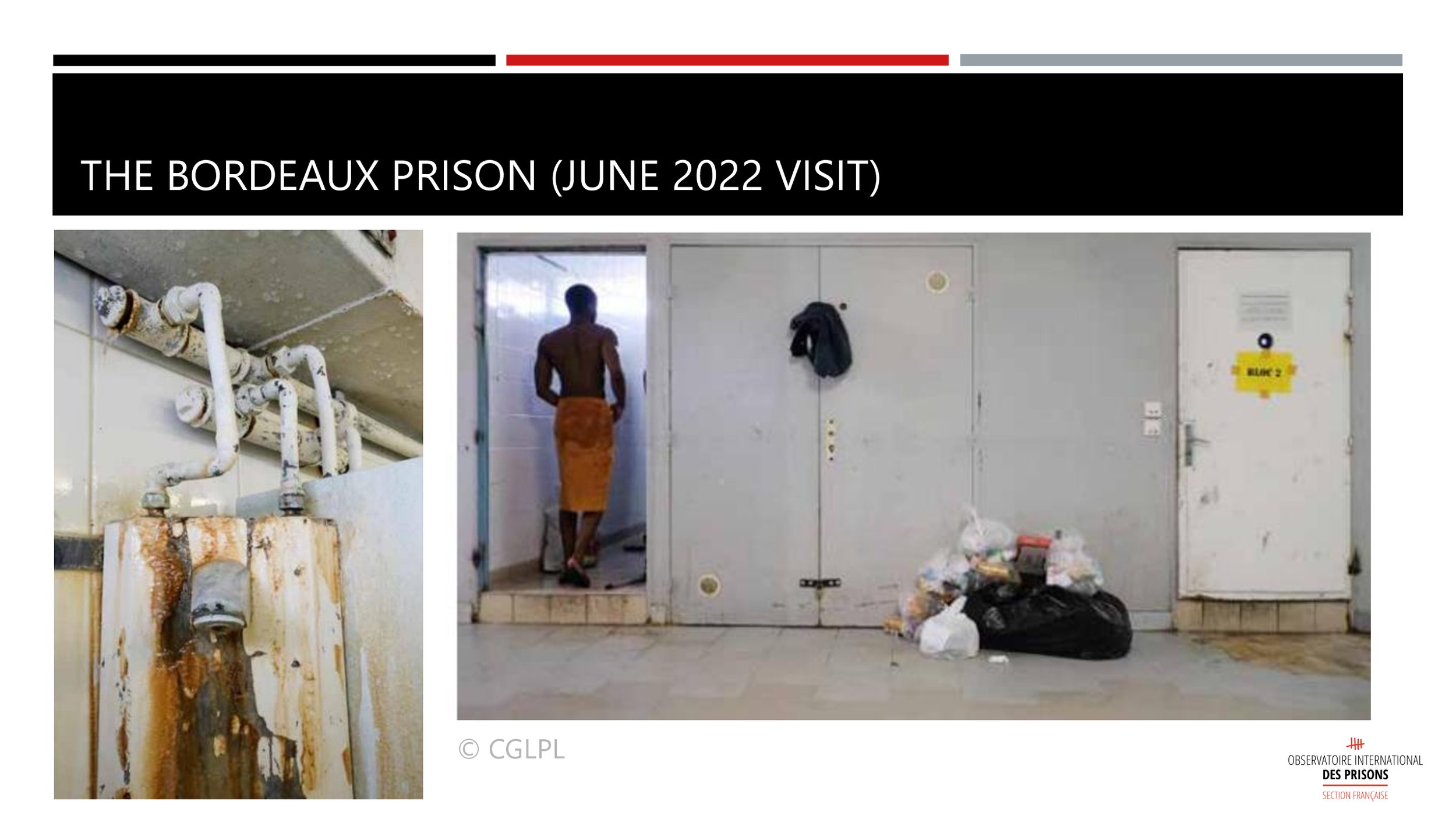

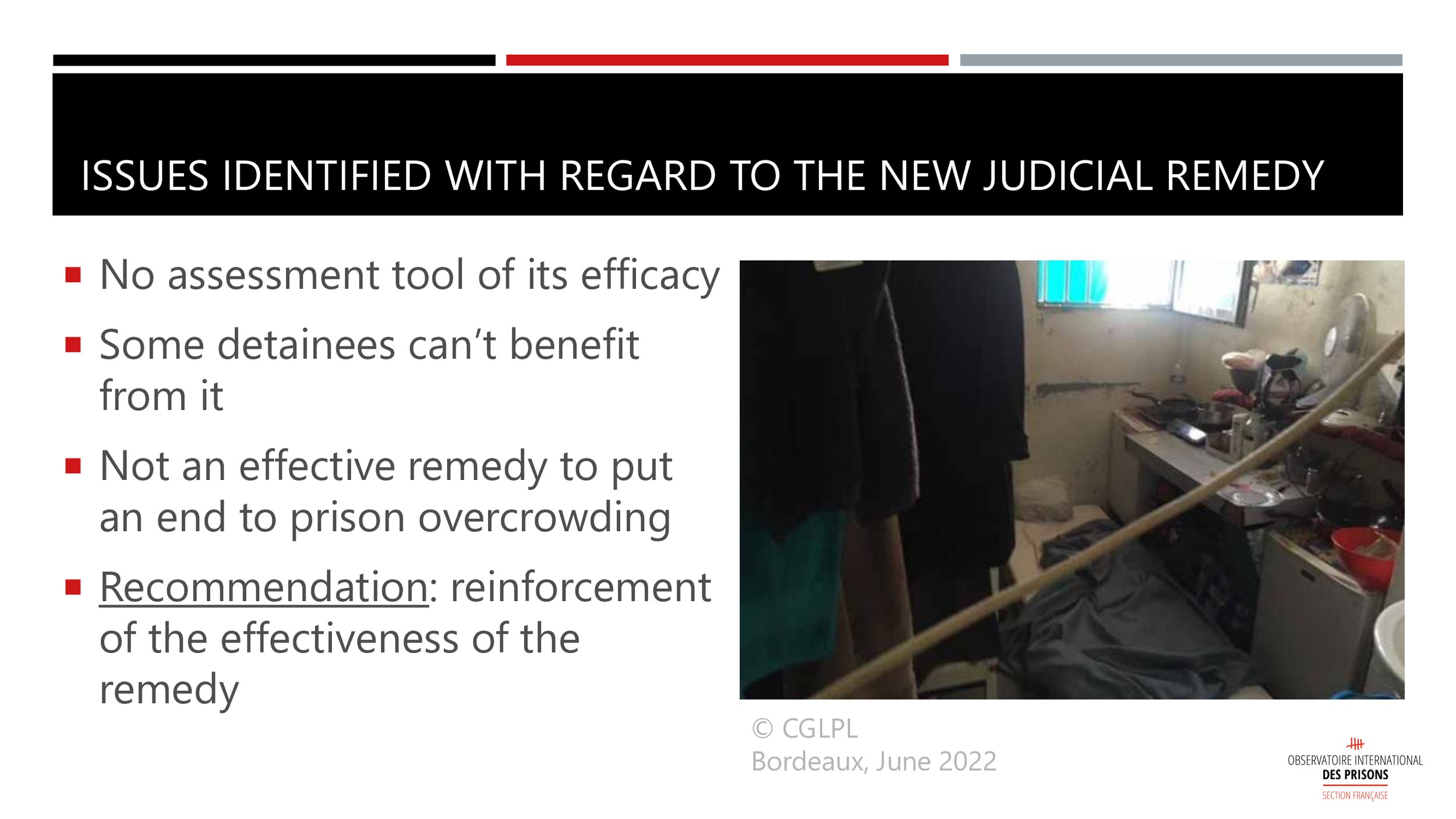

o Degrading living conditions are exacerbated by dilapidated and unsanitary conditions

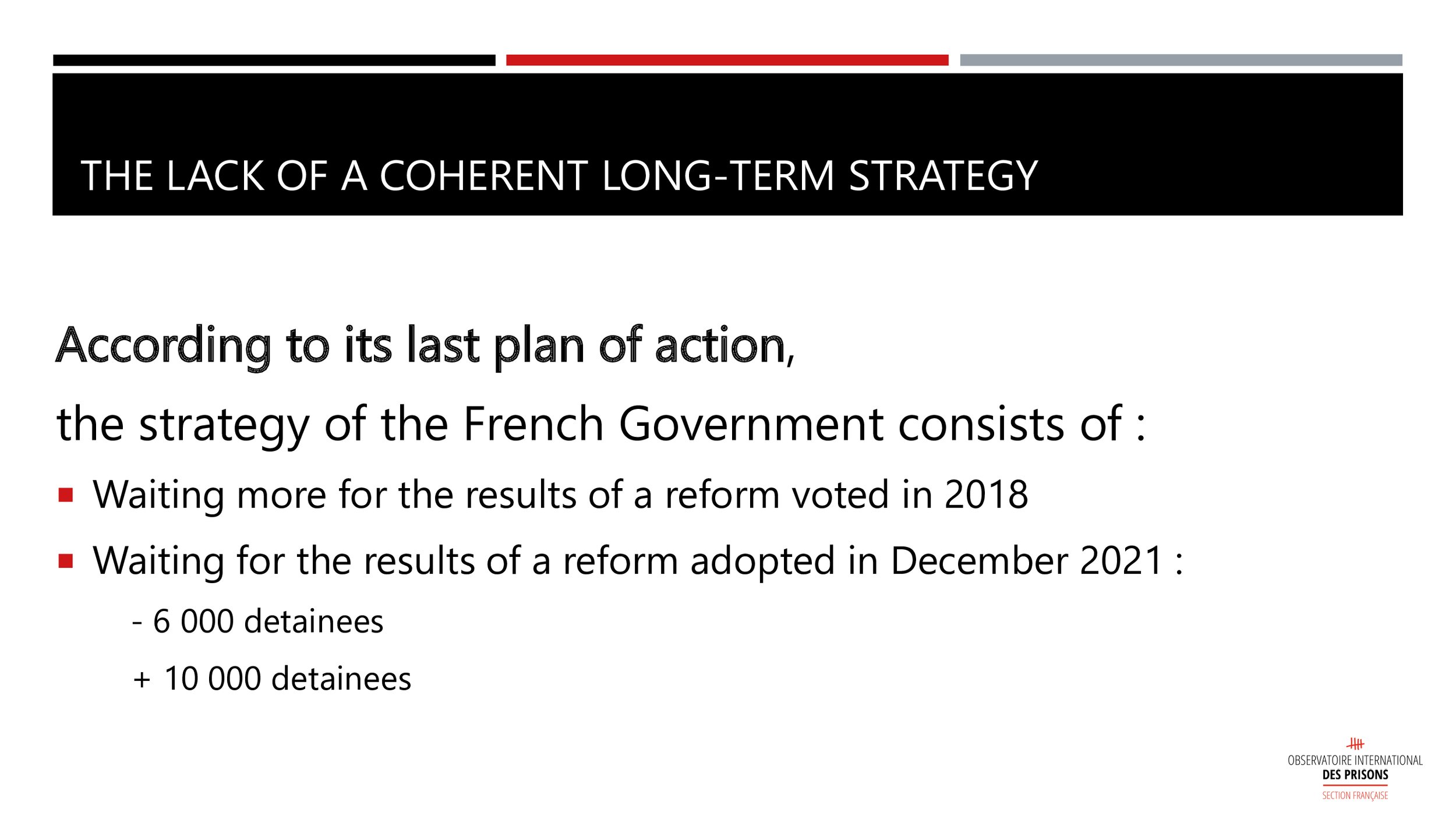

o There is a lack of a coherent long-term strategy

o Constructing new prisons to address prison overcrowding fails to address the structural problem.

o Regarding the new judicial remedy: there is no assessment tool of its’ efficiency; some detainees cannot benefit from it; it is not an effective tool to remedy overcrowding;

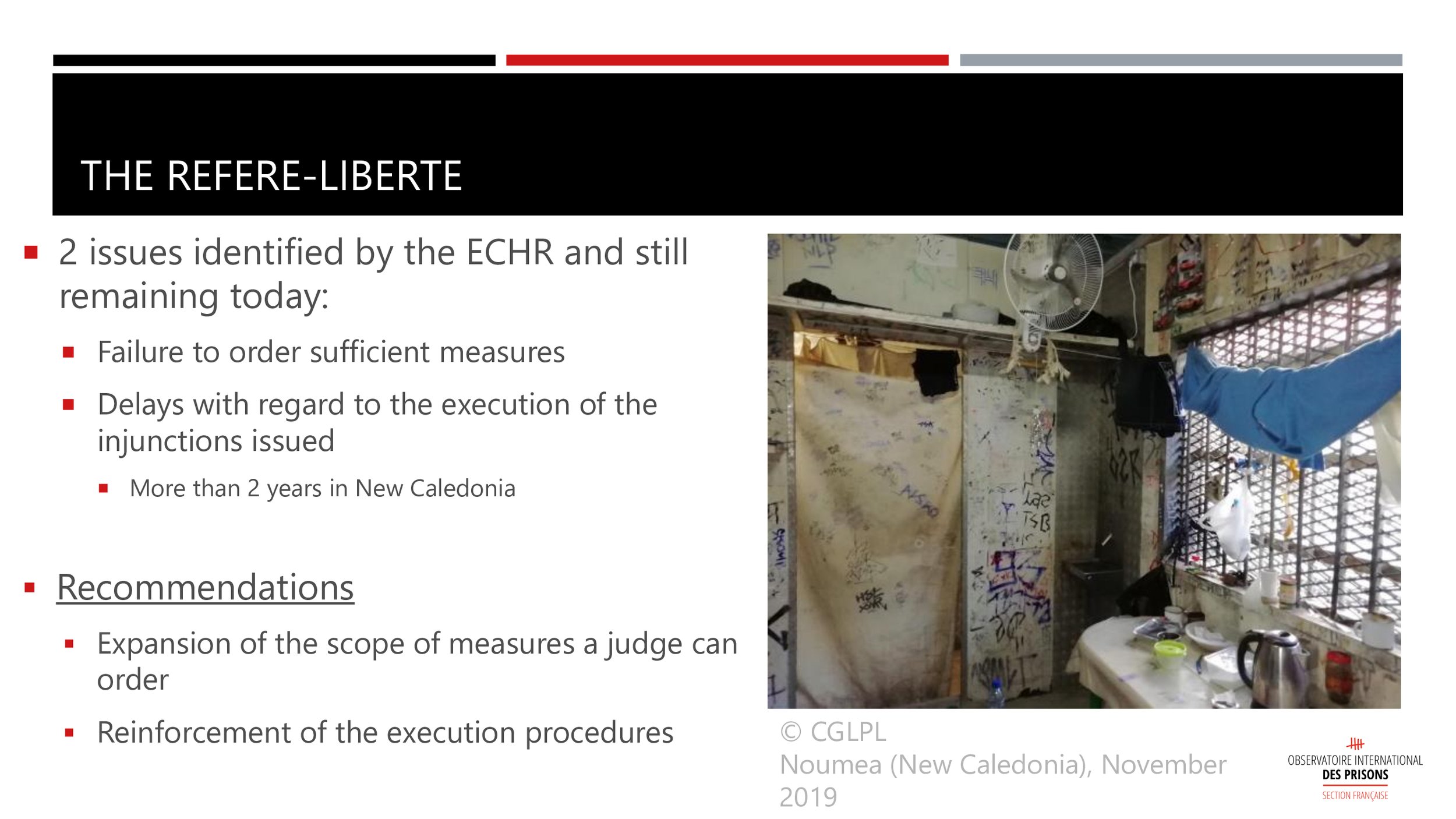

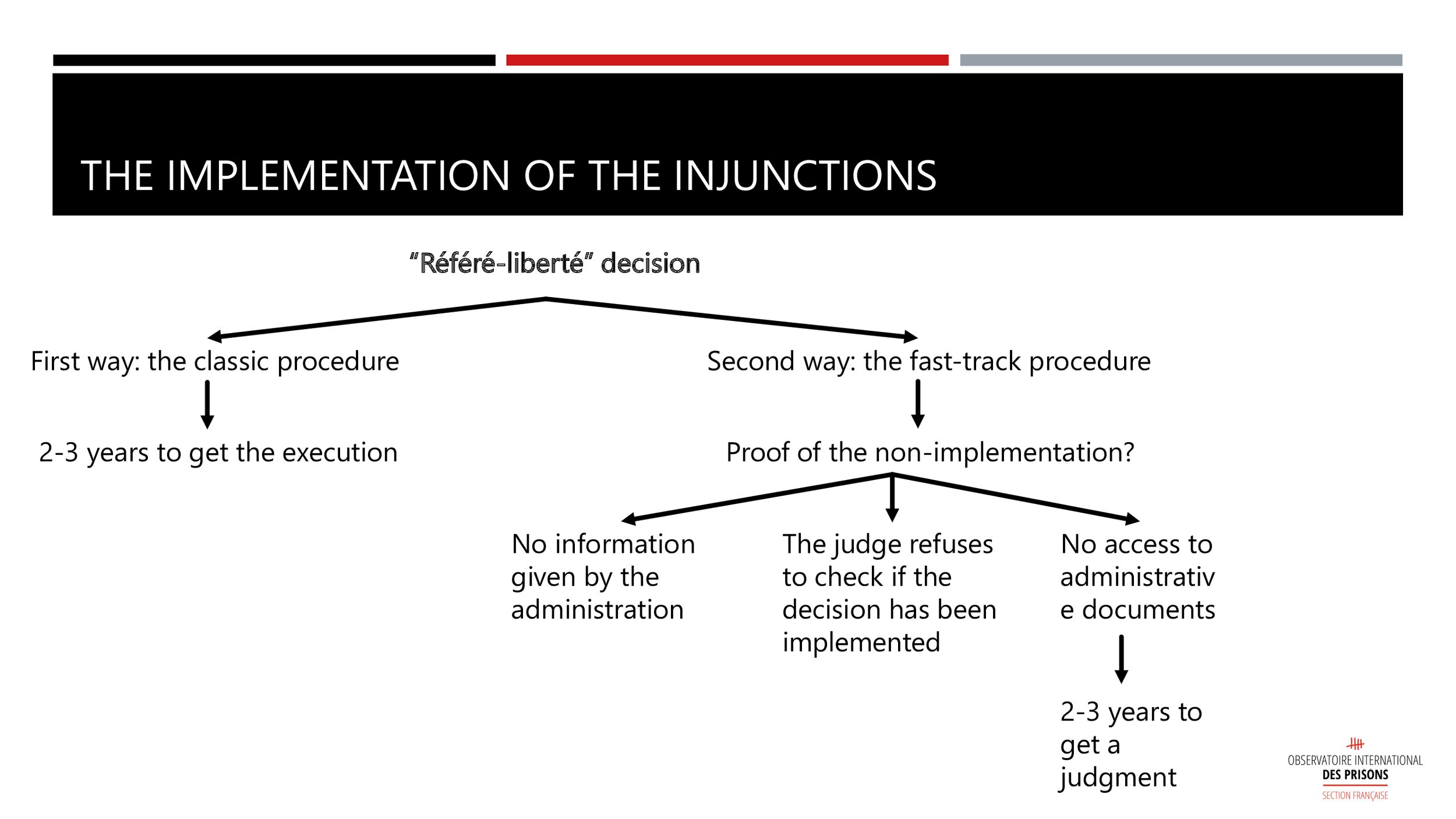

o Regarding the “Référé-liberté” remedy: it is not an effective remedy either, as the issues identified by the ECtHR remain: there are delays with regard to the execution of the injunctions issued and there is a failure to order sufficient measures.

Observatoire International des Prisons outlined their recommendations to participants:

On prison overcrowding

Establishing a binding prison regulation mechanism

Adopting a national action plan ensuring the definitive reduction of prison overcrowding

Discontinuing prison expansion programmes and revising budgetary priorities

On the new judicial remedy

Creating monitoring tools to assess the effectiveness of the remedy

Reinforcing the effectiveness of the remedy

On the preexisting “référé-liberté”

Expanding the scope of measures a judge can order

Reinforcing the execution procedures

Please see the slides for the full Briefing.

Relevant Documents:

NGO/NHRI Communications

Overview of the Case:

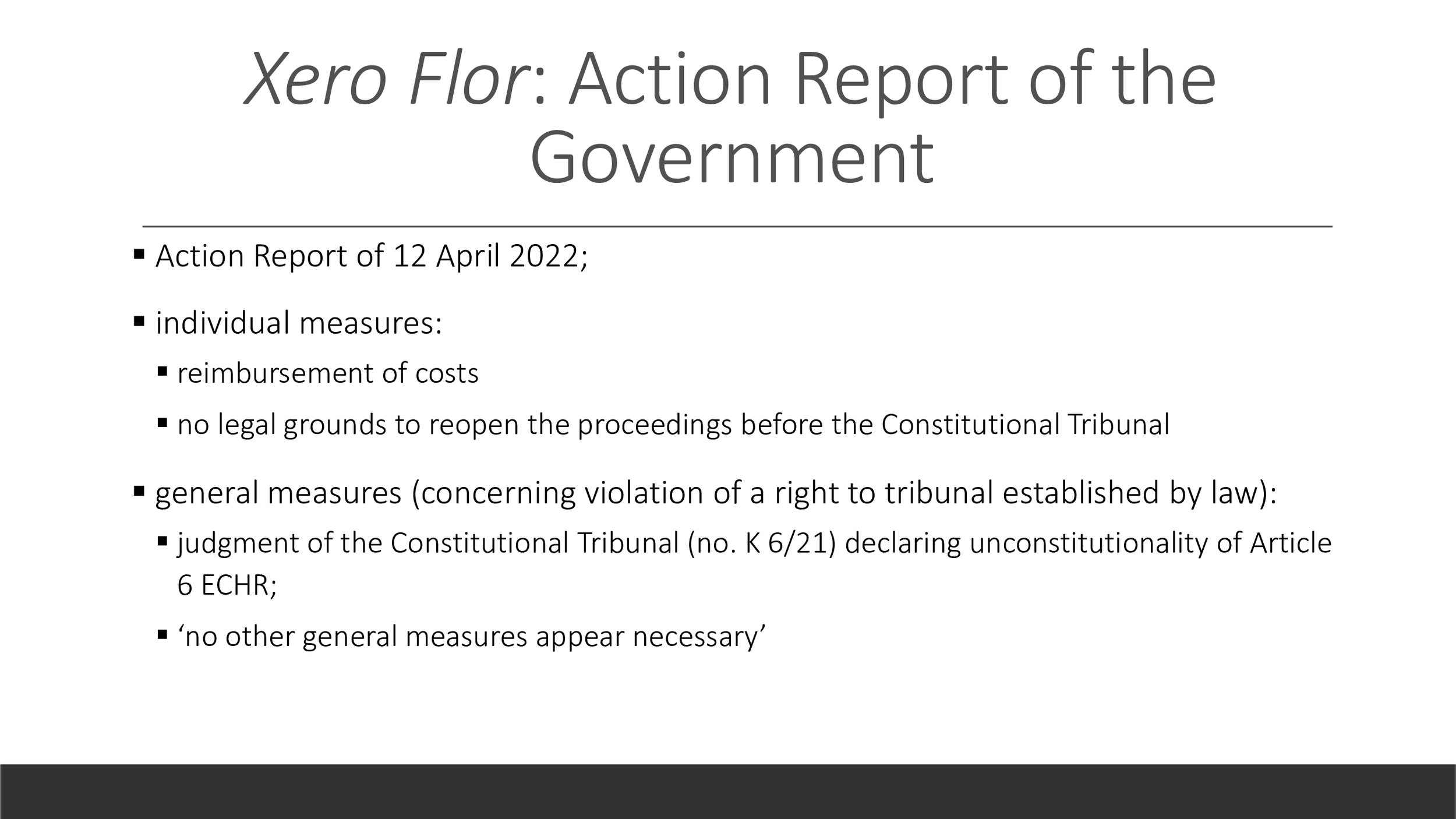

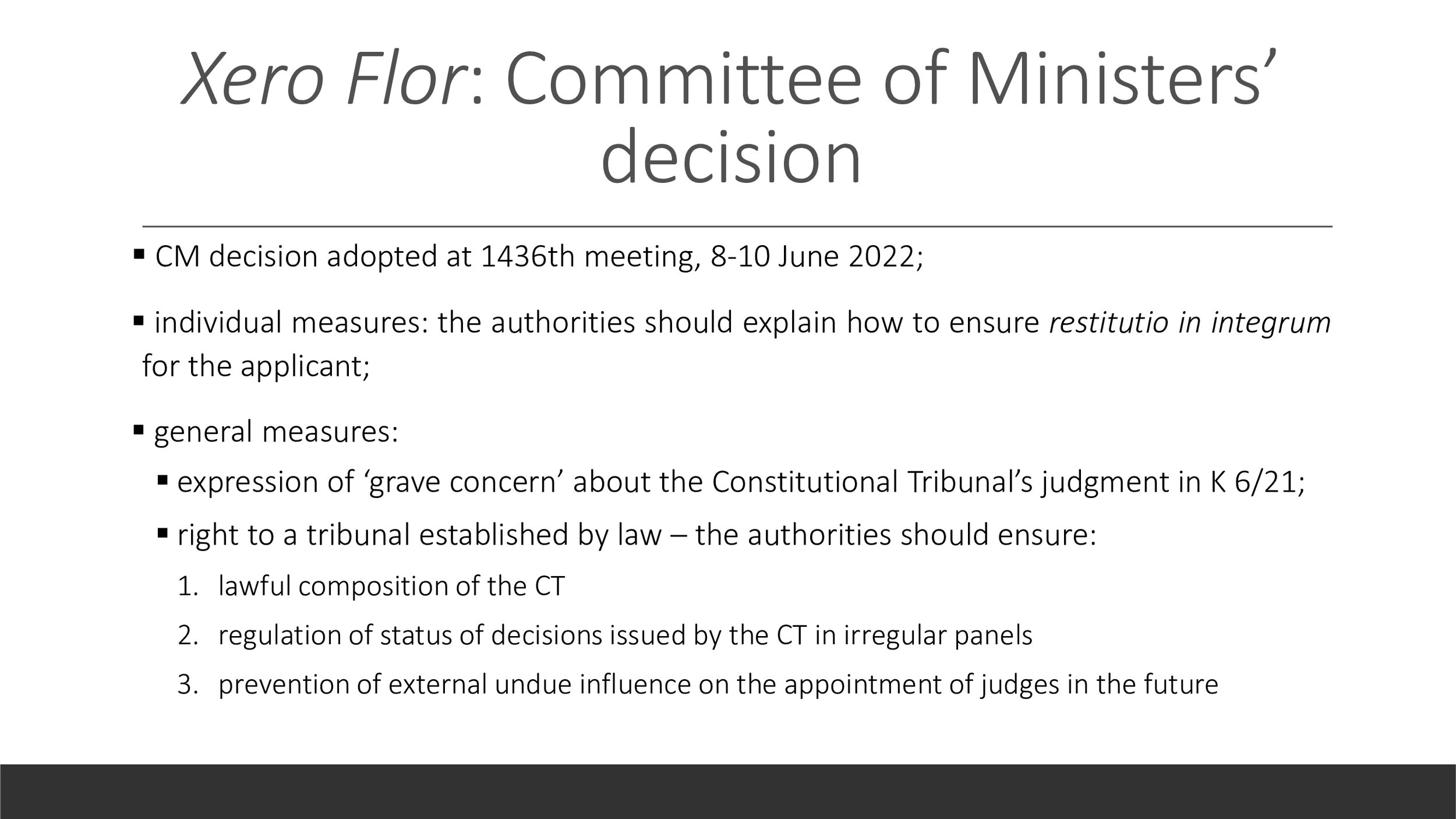

This case concerns an infringement of the applicant company’s right to a fair hearing due to the domestic courts' failure to examine its argument that secondary legislation limiting its right to compensation was unconstitutional. It also concerns the infringement of the applicant company’s right to a tribunal established by law due to the participation of Judge M.M. in the Constitutional Court’s panel that rejected its constitutional complaint.

Helsinki Foundation for Human Rights reminded participants of the Court’s Judgment:

There was a violation of a right to a ‘tribunal established by law’ (Article 6 § 1 ECHR);

The judge was elected with a manifest breach of domestic law;

The violation ‘concerned a fundamental rule of the election procedure, namely the rule that a judge of the Constitutional Court was to be elected by the Sejm whose term of office covered the date on which his seat became vacant.’

An additional violation of Article 6: lack of justification of domestic courts for non-referring legal question to the Constitutional Tribunal

Helsinki Foundation for Human Rights provided participants with recent developments in the case:

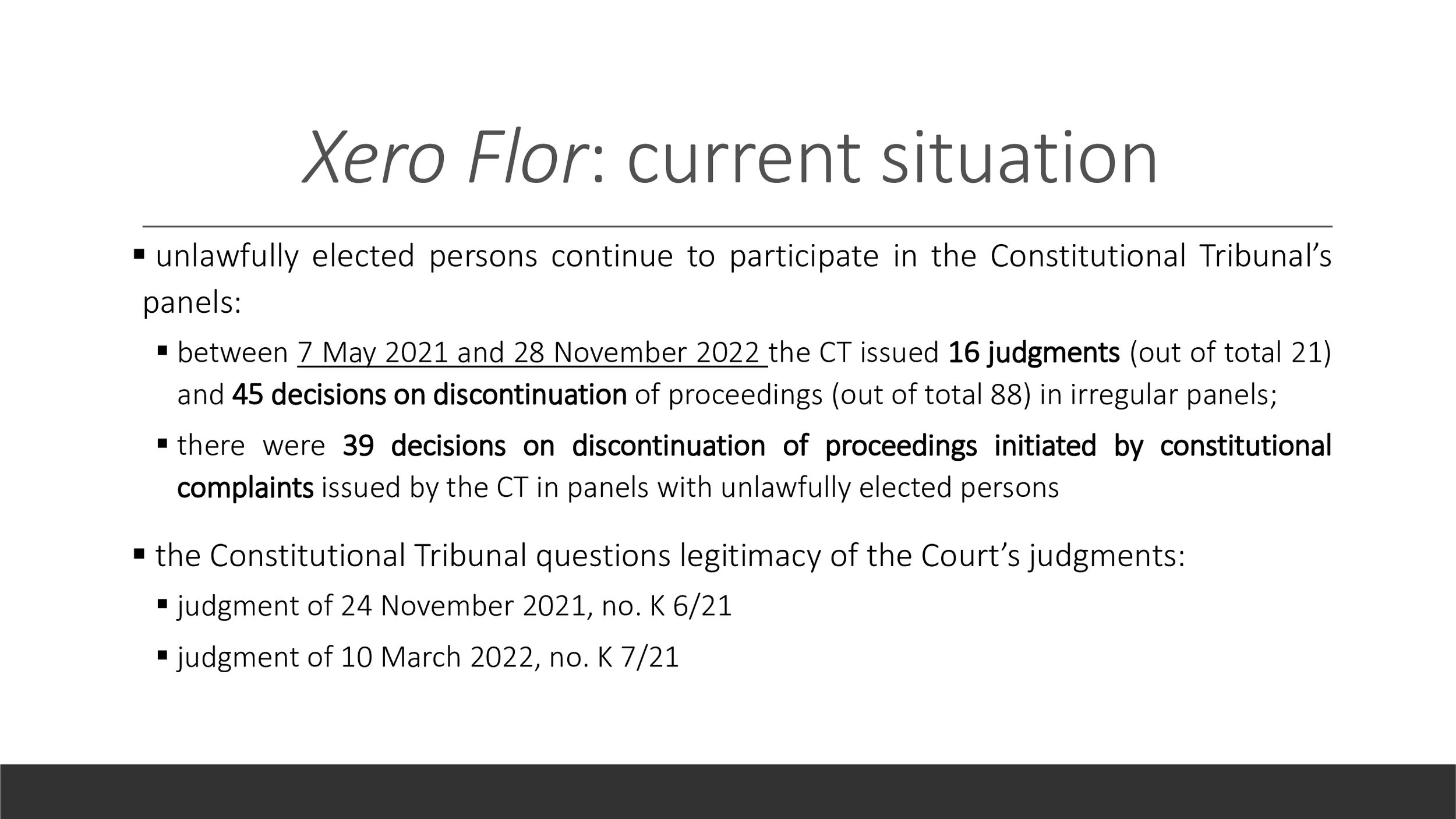

Unlawfully elected persons continue to participate in the Constitutional Tribunal’s panels:

Between 7 May 2021 and 28 November 2022 the CT issued 16 judgments (out of total 21) and 45 decisions on discontinuation of proceedings (out of total 88) in irregular panels;

There were 39 decisions on discontinuation of proceedings initiated by constitutional complaints issued by the CT in panels with unlawfully elected persons

The Constitutional Tribunal questions the legitimacy of the Court’s judgments:

Judgment of 24 November 2021, no. K 6/21

Judgment of 10 March 2022, no. K 7/21

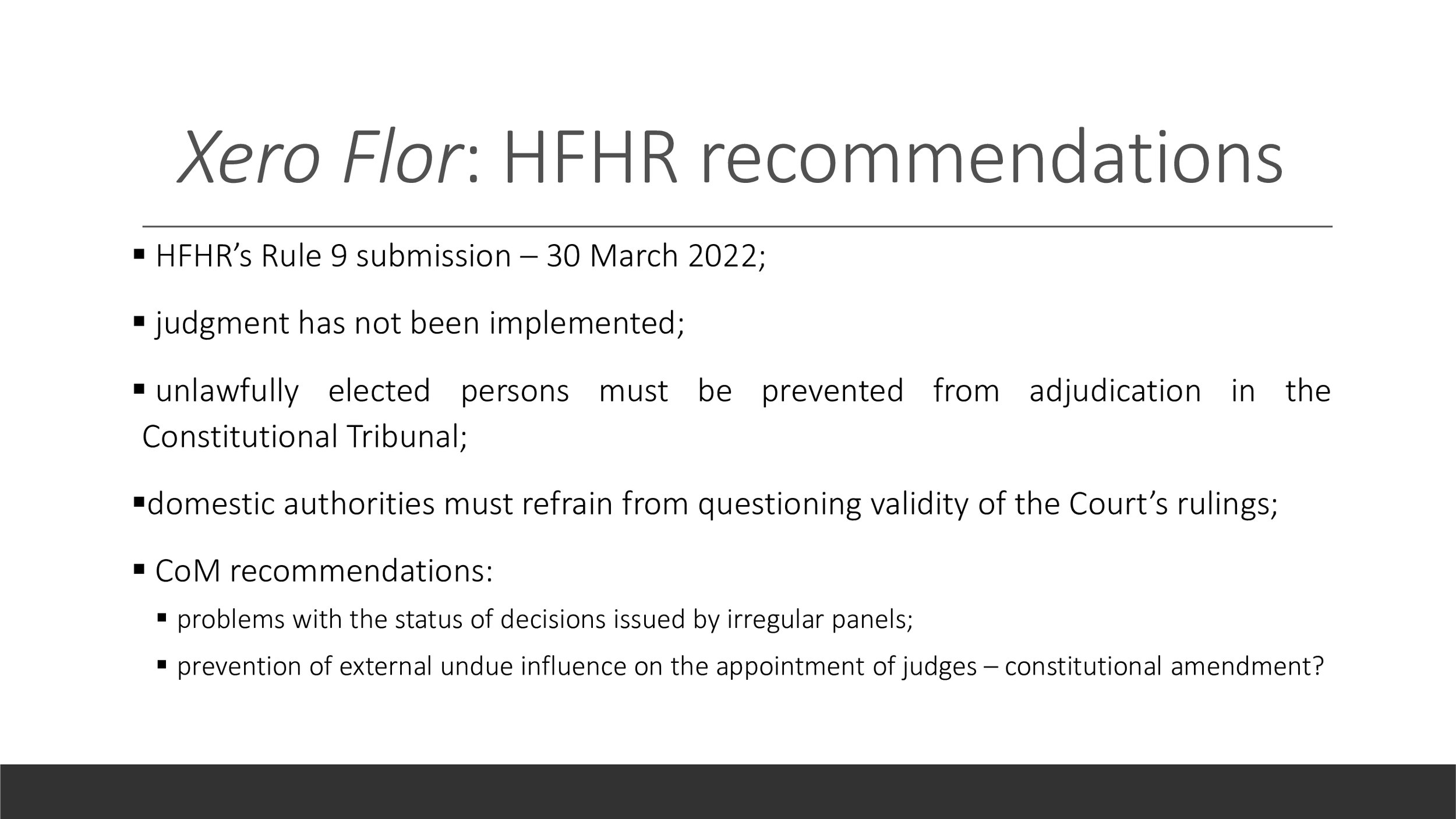

Helsinki Foundation for Human Rights outlines their recommendations for the case:

Unlawfully elected persons must be prevented from adjudication in the Constitutional Tribunal;

Domestic authorities must refrain from questioning the validity of the Court’s rulings;

The CoM should address in recommendations the problems with the status of decisions issued by irregular panels; and the prevention of external undue influence on the appointment of judges.

Relevant Documents

Overview of the Case

This case concerns an infringement of the right to access to the court on account of the premature termination of the applicants’ term of office as vice presidents of a regional court on the basis of temporary legislation in force between 12 August 2017 and 12 February 2018, which did not allow for examination either by an ordinary court or by another body exercising judicial duties

Helsinki Foundation for Human Rights reminded participants of the Court’s Judgment:

The Court ruled that there was a violation of Article 6 § 1 ECHR;

The applicants were completely deprived of access to court with regard to their dismissal from the office of vice presidents of courts;

The Minister’s decision did not contain any statement of reasons;

There was no available protection against arbitrary dismissals;

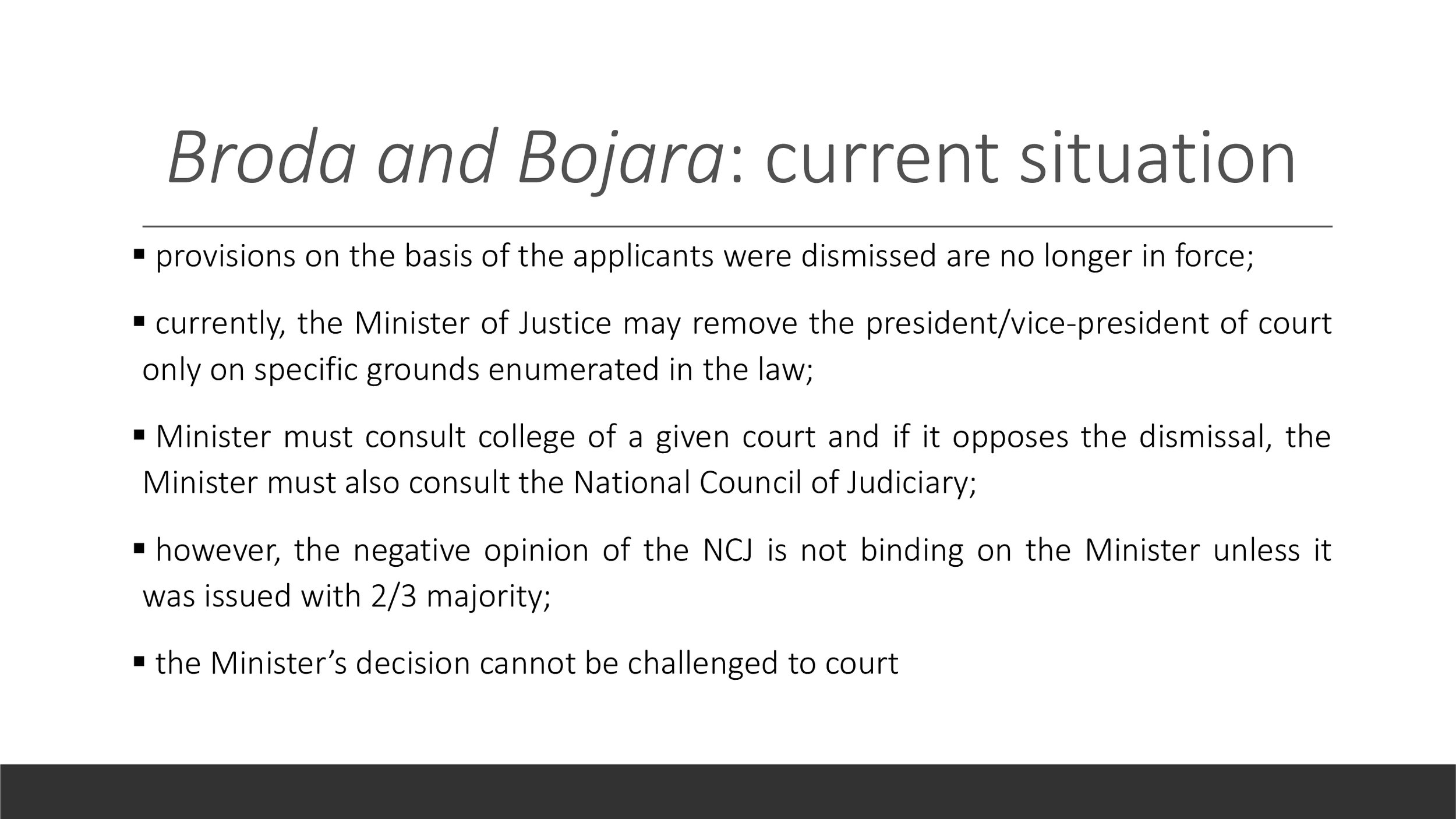

Helsinki Foundation for Human Rights provided participants with recent developments in the case:

The provisions on the basis of which the applicants were dismissed are no longer in force;

Currently, the Minister of Justice may remove the president/vice-president of court only on specific grounds enumerated in the law:

gross or persistent failure to discharge the duties;

remaining vice-president/president in office is incompatible with the interest of administration of justice;

particular inefficiency of president/vice-president in exercising administrative supervision or organising works in the court or lower courts;

voluntary resignation of president/vice-president.

The Minister must consult the college of a given court and if it opposes the dismissal, the Minister must also consult the National Council of Judiciary;

However, the negative opinion of the NCJ is not binding on the Minister unless it was issued with 2/3 majority;

The Minister’s decision cannot be challenged in court.

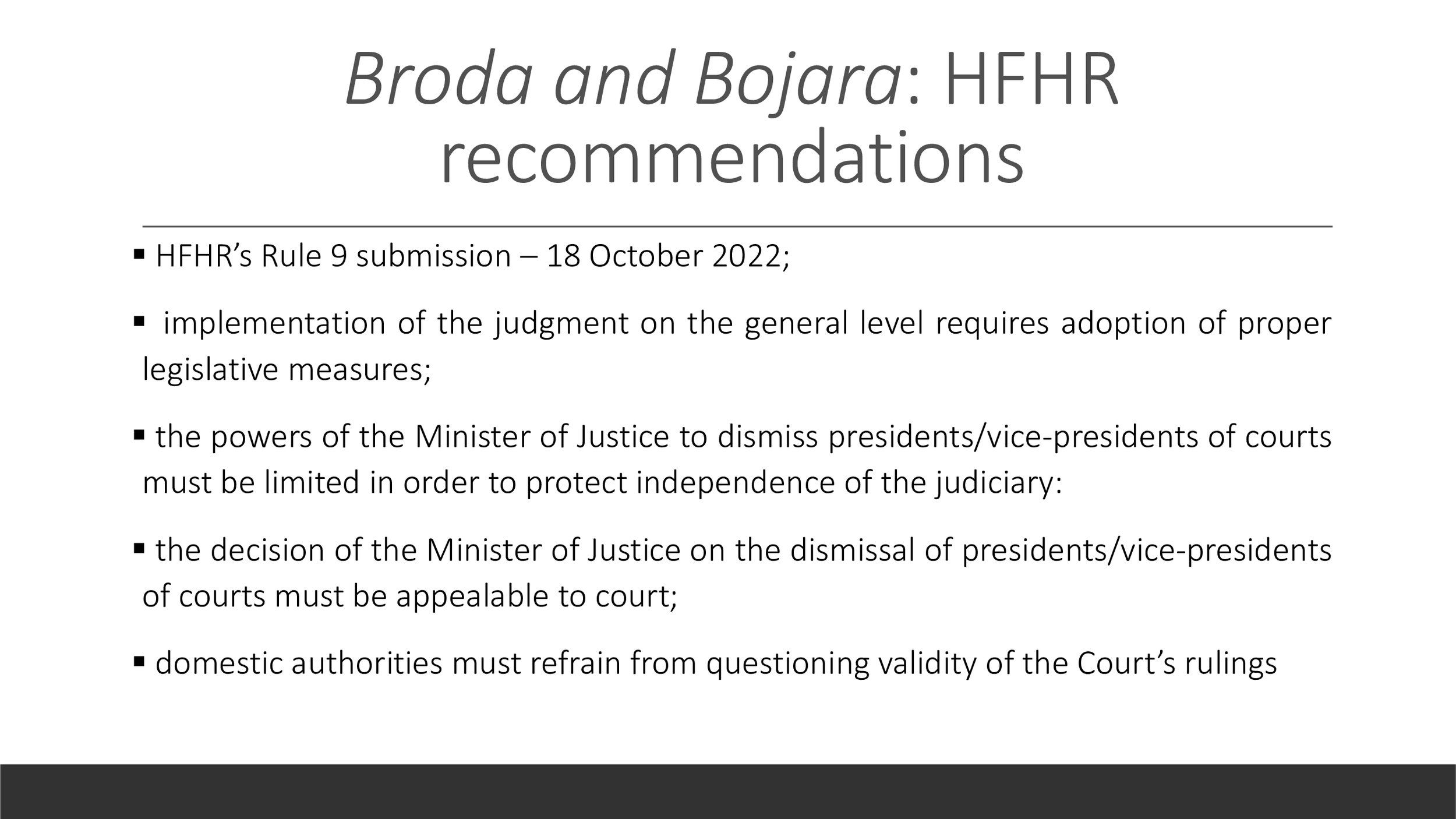

Helsinki Foundation for Human Rights outlines their recommendations for the case:

Implementation of the judgment on the general level requires the adoption of proper legislative measures;

There is a need for legislative change: the powers of the Minister of Justice to dismiss presidents/vice-presidents of courts must be limited in order to protect independence of the judiciary:

negative opinion of the NCJ should be binding on the Minister of Justice (as it was until 2017);

NCJ must be an independent and lawfully constituted organ;

limitation of the MoJ’s discretion in the appointment of court presidents will also be advisable

The decision of the Minister of Justice on the dismissal of presidents/vice-presidents of courts must be appealable to court;

Domestic authorities must refrain from questioning the validity of the Court’s rulings.

Please see the slides for the full Briefing.

Relevant Documents

NGO/NHRI Communications

Reczkowicz group v Poland

Overview of the Case

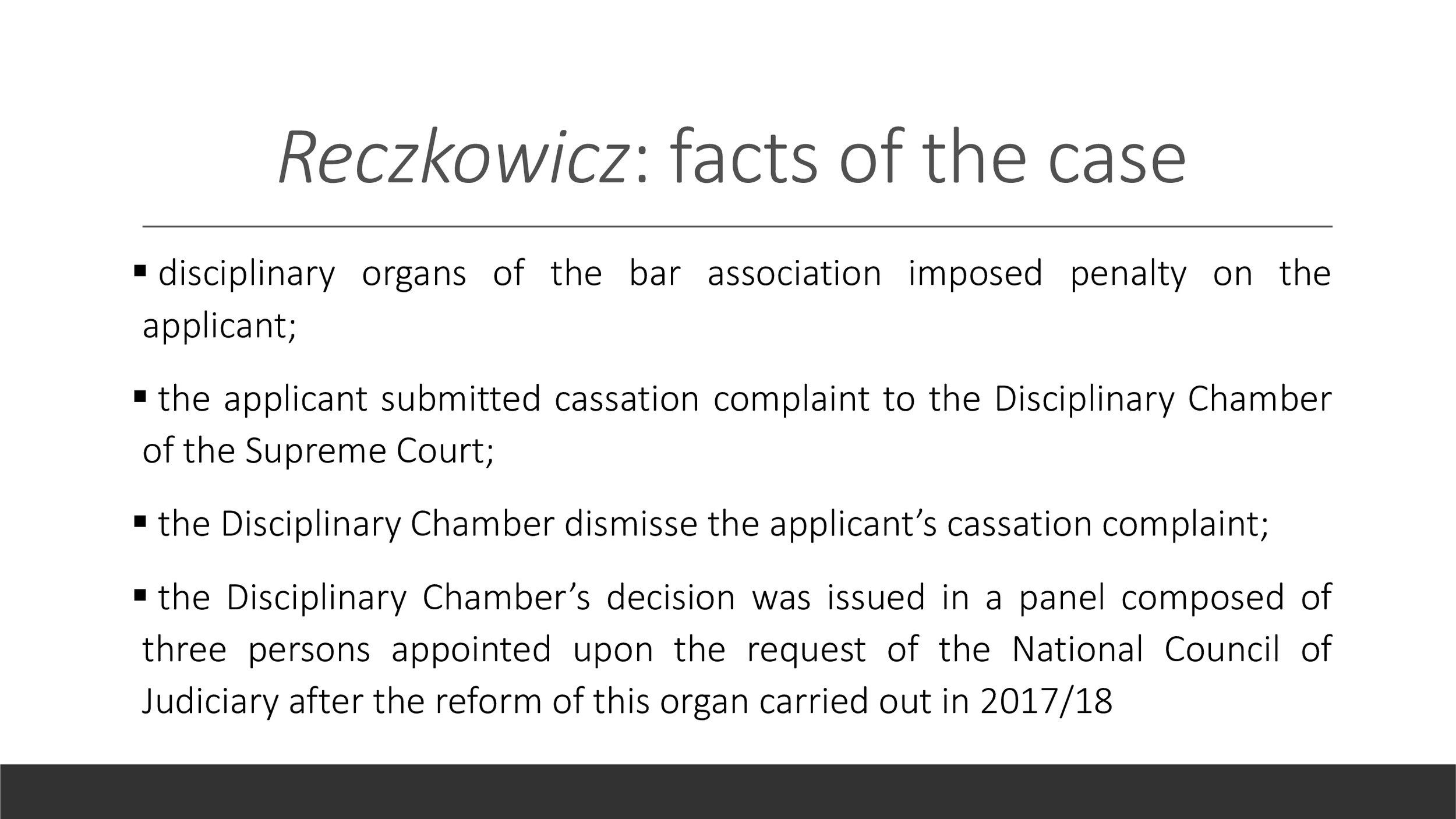

This case concerns an infringement of the right to tribunal established by law, due to the fact that the judges of the Disciplinary Chamber in the Supreme Court that dismissed the applicant’s cassation appeal against disciplinary penalty in 2019 were appointed in a deficient judicial appointment procedure involving the National Council of the Judiciary lacking independence from legislature and executive (violation of Article 6 of the Convention).

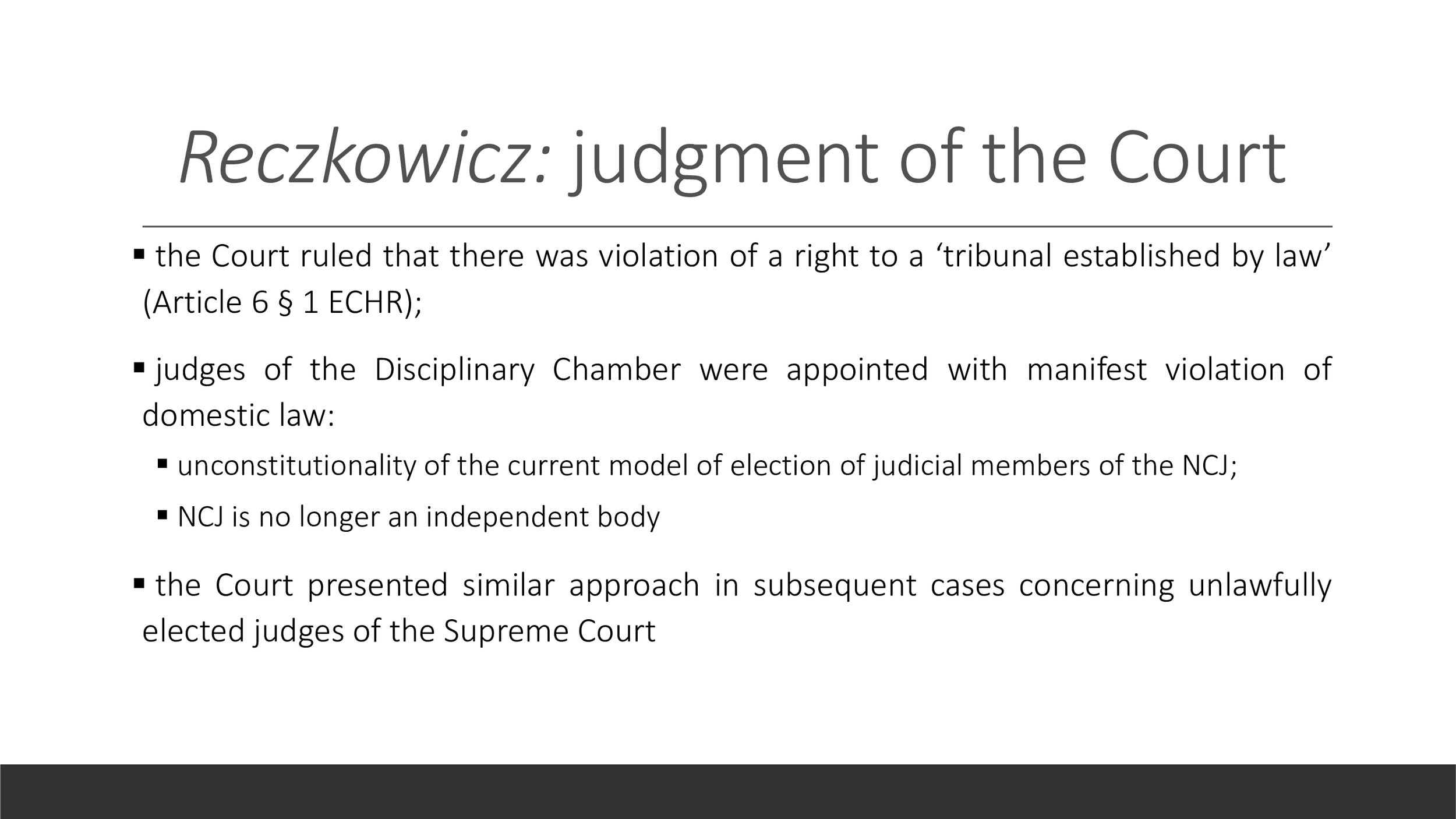

Helsinki Foundation for Human Rights reminded participants of the Court’s judgment:

The Court ruled that there was a violation of a right to a ‘tribunal established by law’ (Article 6 § 1 ECHR);

Judges of the Disciplinary Chamber were appointed with manifest violations of domestic law;

Unconstitutionality of the current model of the election of judicial members of the National Council of the Judiciary (NCJ);

NCJ is no longer an independent body;

The Court presented a similar approach in subsequent cases concerning unlawfully elected judges of the Supreme Court.

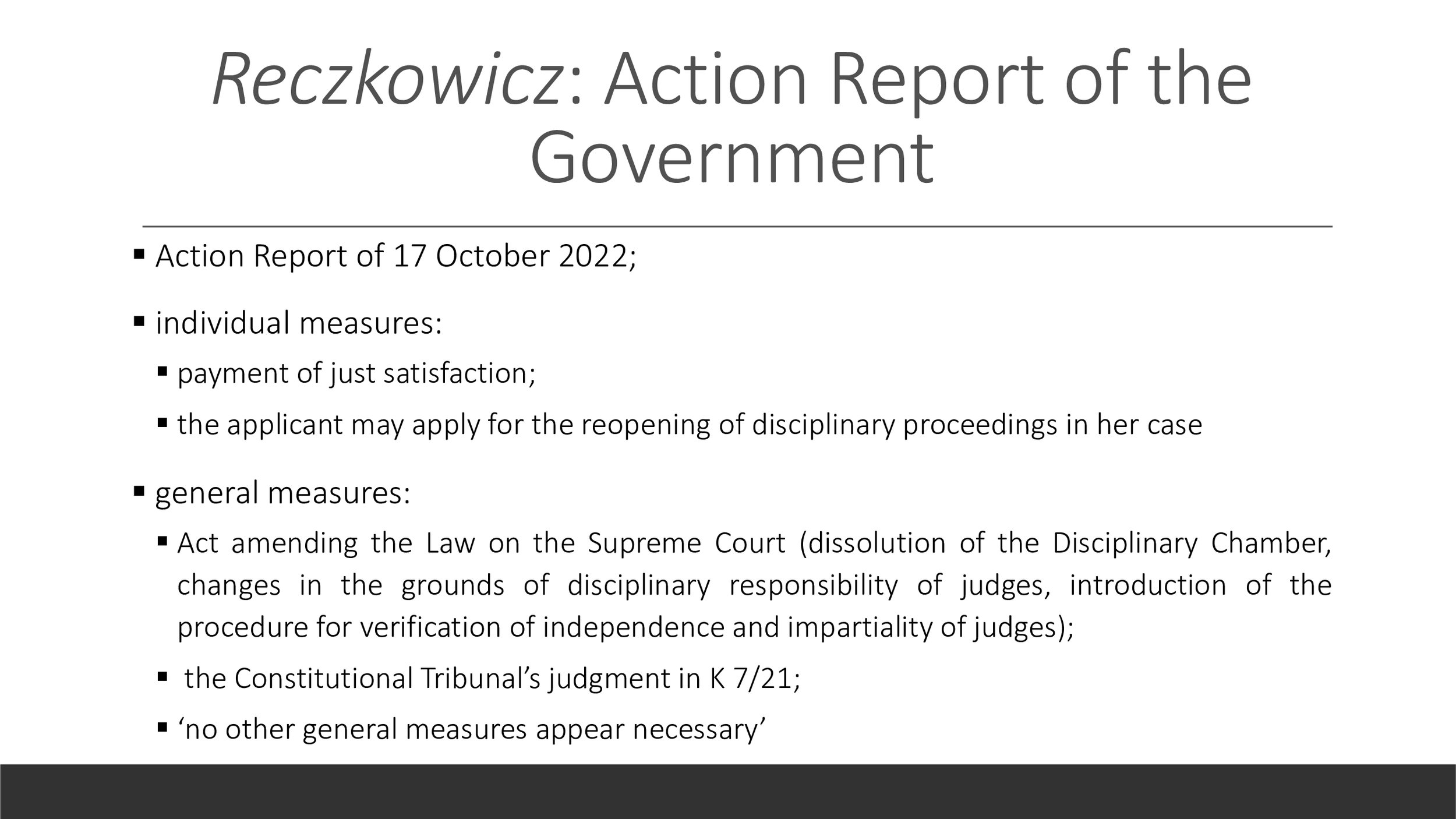

Helsinki Foundation for Human Rights provided participants with recent developments in the case:

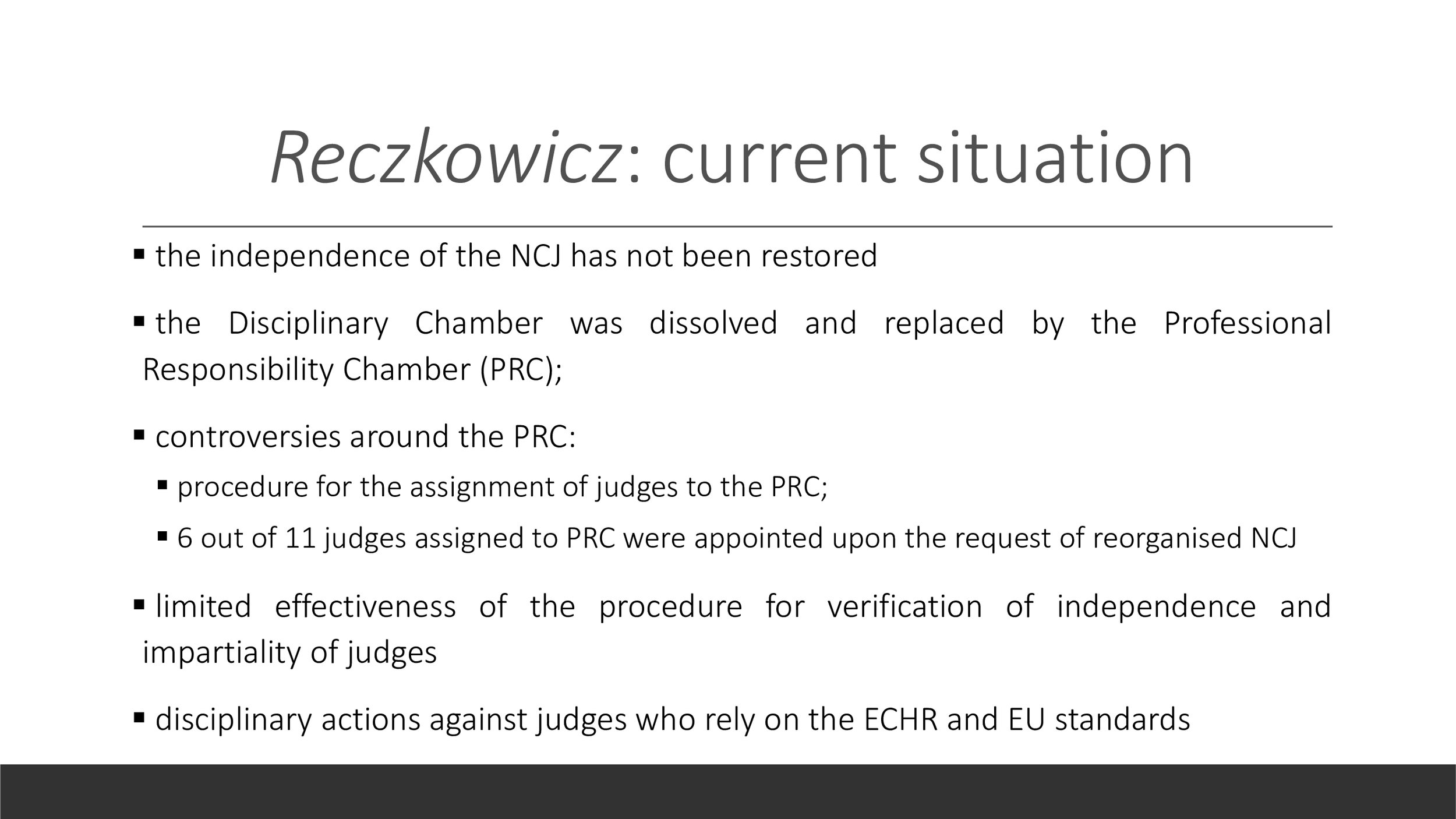

The independence of the NCJ has not been restored;

The Disciplinary Chamber was dissolved and replaced by the Professional Responsibility Chamber (PRC);

There are controversies around the PRC with regard to:

The procedure for the assignment of judges to the PRC;

6 out of 11 judges assigned to PRC were appointed upon the request of reorganised NCJ.

Limited effectiveness of the procedure for verification of independence and impartiality of judges;

Disciplinary actions against judges who rely on the ECHR and EU standards.

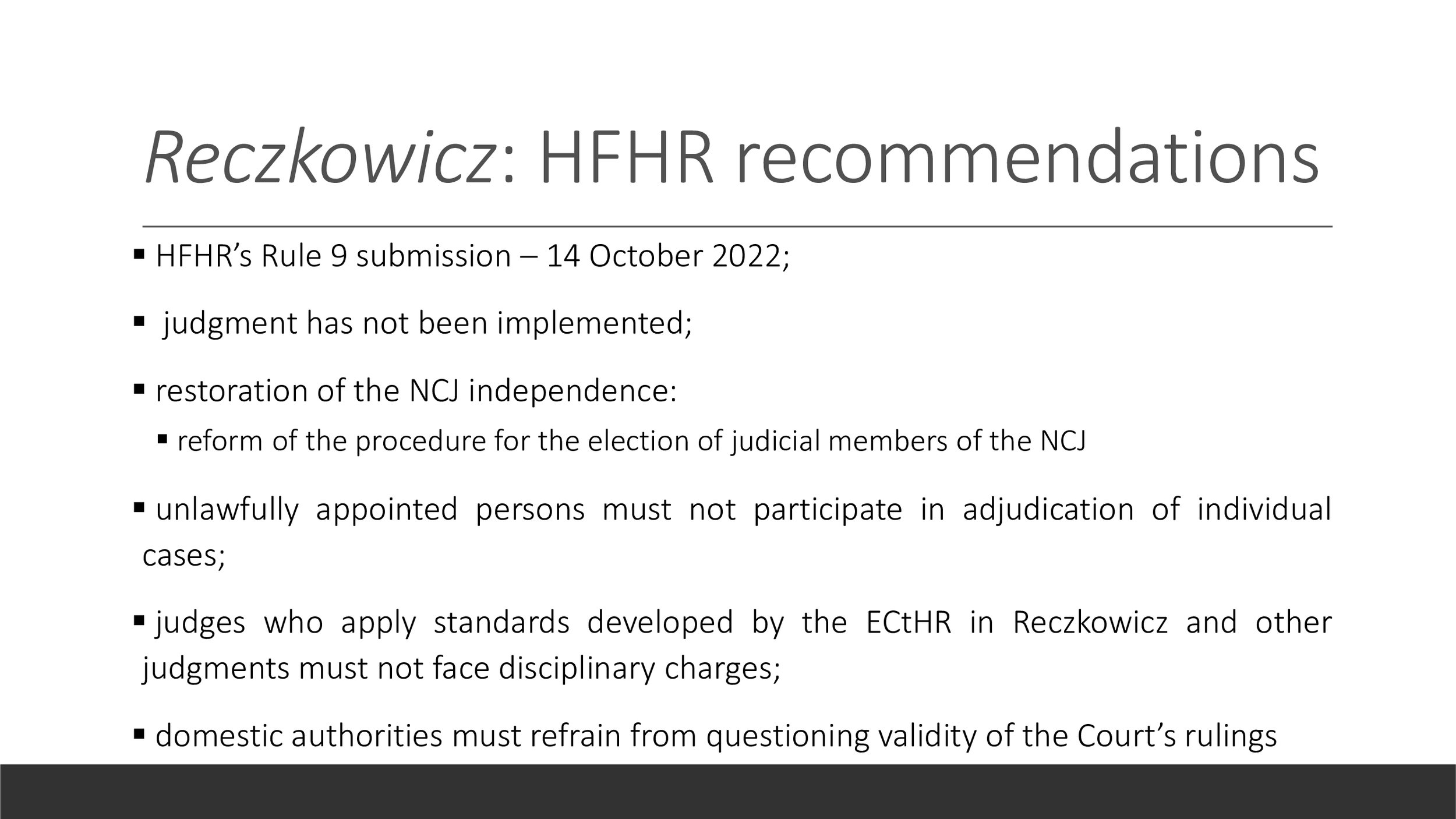

Helsinki Foundation for Human Rights outlines their recommendations for the case; the Committee of Ministers should call for:

Restoration of the NCJ independence through reform of the procedure for the election of judicial members of the NCJ.

Unlawfully appointed persons must not participate in adjudication of individual cases;

The status of judgments issued by unlawfully appointed persons must be regulated;

Judges who apply standards developed by the ECtHR in Reczkowicz and other judgments must not face disciplinary charges;

Domestic authorities must refrain from questioning validity of the Court’s rulings.

HFHR’s Rule 9 submission of 14 October 2022 is available here.

Please see the slides for the full Briefing.

Relevant Documents

Applicant Communications

NGO/NHRI Communications

Overview of the Case

This group of cases concerns the failure of the authorities to protect women (the applicants or their female relatives) from domestic violence, despite having been reasonably informed of the real and imminent risks and threats (Articles 2 and 3). In the cases of Opuz, M.G. and Halime Kılıç, the Court also found that the failure to protect the women was discriminatory on grounds of gender (violation of Article 14 in conjunction with Articles 2 and 3).

Mor Çatı provided an update and recommendations for individual measures in the M.G. case, after reminding participants that, in the CM’s latest decision, it had reiterated “the importance of continuing to monitor the applicants’ safety, since their former husbands are not in detention:

The appeal proceedings are still pending and the applicant’s ex-husband has not been detained and continues to make threats against her.

The national authorities should speed up the proceedings in order to ensure that the perpetrator is brought to justice effectively, and should also urgently take measures to ensure the applicant’s safety.

Mor Çatı reminded participants that, on 20 March 2021, Turkey decided to withdraw from the Istanbul Convention. In relation to the latest Action Plan, Mor Çatı stated that the existing laws are presented as general measures; however, the main issue on the ground is the lack of implementation of these laws. There are no monitoring and evaluation processes to achieve standards in the implementation of the laws and there are no any sanctions against bad practitioners.

Mor Çatı provided updated information on the following areas:

Barriers to justice

Victims hesitate to file complaints due to distrust of system, deterrent behavior of public officials, lack of information, lack of qualified free legal support, long duration of the legal procedures, lack of protection and social and psychological support during long duration of legal procedures.

Reasonable time to ensure that investigative procedural steps are completed

Taking the statement of the suspect takes up to 1 year or more.

The trial process: The local court proceedings takes up to 1-2 years. It can take up to 2-3 years on average to conclude appealed case decisions. It can take approximately about 2-3 more years for cases before the Court of Cassation.

Risk assessment

The Penal Code does not include a specific regulation for risk assessment in the context of domestic violence offence, these measures are only available in the Law No. 6284.

Prosecutor’s Offices, Criminal Courts and Family Courts fail to conduct risk assessment in respect of perpetrators who repeatedly commit violent crimes against women.

Implementation of arrest warrants

Law enforcement do not conduct an effective search to execute the arrest warrants; arrests are made if the perpetrator is found by chance.

Arrests for warrants are sometimes never executed and years may go by. Those who are not arrested until the statute of limitations is expired have their

sentence repealed.

Non-Deterrent Effect of Sentences and de facto impunity

Sentences are usually imposed at the lower limit and a discretionary mitigation (mitigation for good conduct) is applied.

Mitigated sentences given for the offenses of bodily harm with intent, threat and insult are usually commuted to a fine, followed by a deferment of the announcement of the verdict, as a result of which even the fine is not paid de facto.

Discretionary mitigation and mitigation of sentences on account of unjust provocation

In the case of more serious offenses where the convict has started to serve the sentence, the full term of imprisonment is not served due to the practice of conditional release; due to legal regulations such as suspension of sentence, de facto impunity takes place even when the convict has started to serve the sentence.

Contrary to the legal provisions, the mitigation of sentences on account of “unjust provocation” results in a significant reduction in sentences based on a

sexist practice.

Grounds for impunity

The courts ignore less serious offenses (e.g. offense of libel) when there is more than one type of crime is inflicted by the perpetrator.

Court decisions are influenced by the physical appearance (e.g. well-dressed etc.) and economic class of the perpetrator.

It is observed that the grounds for acquittals often refer to expressions such as “defendant’s persistent denial of charges”; and the presumption of innocence is used as a legal cover-up for impunity.

Mor Çatı set out their recommendations for the implementation of the Opuz group of cases. The CM should call on the authorities to:

Re-become a party to Istanbul Convention.

Establish state-wide effective, comprehensive and coordinated policies encompassing all relevant measures to prevent and combat all forms of violence.

In order to ensure an effective implementation of both the Penal Code and the Law No.6284, the state should present data on the existing official complaint mechanisms, how many complaints have been filed to these mechanisms and what the results were and on monitoring and evaluation mechanisms for the implementation of the relevant legal framework, including the number and result of investigations towards public officers for bad practice. The statistical data should be disaggregated by gender, age, type and frequency of violence, relationship between perpetrator and survivor, geographical location and disability status.

Ensure that bad practices by public officials are sanctioned.

Facilitate for women the right to file complaints also with the police stations in their own neighborhoods rather than making mandatory referrals to specialised units such as the Bureaus of Combatting Domestic Violence and Violence Against Women.

Promptly provide legal support in criminal cases to victims without administrative obstacles.

Take measures to ensure that investigative procedural steps are completed within 6 months to maximum 1 year, including by taking the statement of the suspect at the investigation stage and collecting evidence or conducting an inquiry within a reasonable time if the suspect cannot be reached.

Provide data on the number of cases where risk assessment is conducted and detailed information on the tools used for risk assessment.

Provide information on how and to what extent the 2020 Circular is enforced and on sanctions for non-implementation.

Carry out a holistic risk assessment that includes a danger assessment, tailored specifically to cases of violence against women.

Take measures to ensure that arrest warrants are implemented effectively.

Provide data on how many arrest warrants are given, how many of them are for convicted perpetrators, how many of these warrants are executed, the mechanisms implemented to execute arrest warrants

Take measures (awareness-raising, training and capacity-building measures, etc.) to avoid sexist practices in the mitigation of sentences and judgments.

Provide information on what legislative measures are envisaged to ensure that investigations in less serious offences are initiated even in the absence of a complaint by domestic violence victim.

Take measures to enable effective implementation of sentences (e.g. To prevent the de facto impunity as a result of converting fines to fees.)

Provide data on the implementation of the recent changes in the Penal Code regarding the application of “good conduct” in cases of violence against women.

Please see the slides for the full Briefing.

Relevant Documents

NGO/NHRI Communications

CM Decisions